Key Takeaways

Polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) is a term used to describe a confusing collection of symptoms. It’s a metabolic and hormone disorder that affects around 6 to 12% of women of childbearing age.

What most of these women don’t know is that diet and lifestyle changes can be used to keep this syndrome in check. As a Nutritionist with PCOS, I’ve done it myself. Using the latest evidence-based information and proven practical tools, my free PCOS food plans have now helped over 100,000 other women too.

My free 30-Day PCOS Diet Challenge and my free 3-Day PCOS meal plan are great first steps towards taking back control of your health and fertility.

What is PCOS and How to Get Diagnosed

For decades, experts have disagreed about how best to diagnose polycystic ovary syndrome. However, the most up-to-date recommendation is to use the modified Rotterdam Consensus [1, 2]. These require two of the following three criteria:

- Irregular or absent periods

- Elevated androgen levels

- The presence of polycystic ovaries (seen via ultrasound)

Because only two out of three criteria are needed, there are four sub-types of PCOS:

Frank PCOS (a.k.a. “Full-blown” PCOS)

- Irregular periods

- Elevated androgens

- Polycystic ovaries

Ovulatory PCOS

- Regular periods

- Elevated androgens

- Polycystic ovaries

Non-PCO PCOS

- Irregular periods

- Elevated androgens

- Normal ovaries

Normoandrogenic PCOS

- Irregular periods

- Normal androgen levels

- Polycystic ovaries

Women with Frank PCOS have the greatest metabolic health risks. By comparison, PCOS women with normal androgen levels have fewer health risks [3, 4]. The Ovulatory PCOS sub-type shows that you can still have PCOS even if you have a regular period. And despite the confusing name, the non-PCO subtype shows that you can still have PCOS and not have polycystic ovaries!

It’s worth noting also, that despite the common perception, your body weight is not part of the diagnostic criteria. Many doctors only suspect PCOS in the case of overweight patients. This means that lean women are more likely to have their diagnosis missed. This is what happened to me and many other women I meet through my free 30-Day PCOS Diet Challenge.

The other important thing to keep in mind is that the Rotterdam criteria are used by doctors and medical researchers. But they’re not that useful from a patient’s perspective. That’s why many people are drawn to the four types of PCOS used in naturopathic medicine. These alternative sub-types of PCOS tend to focus more on the underlying drivers of your symptoms.

Summary

PCOS is best diagnosed using the modified Rotterdam criteria. These enable doctors to identify four sub-types of PCOS.

Common PCOS Symptoms

PCOS adversely affects hormonal balance. This can result in a wide range of seemingly disparate symptoms. The most common signs of PCOS include:

- Irregular or absent periods

- Heavy or painful bleeds

- Difficulty losing weight (and keeping it off)

- Unwanted hair growth, especially on the face

- Thinning hair or hair loss (sometimes male-pattern baldness)

- Oily skin, acne, and eczema

- Dark skin patches in the neck, groin, or under the breast

- Insomnia

- Anxiety and depression

Summary

Problems with menstruation, body weight, hair, and skin are common signs of PCOS.

Associated Health Risks

Understandably, the symptoms of PCOS can cause low self-esteem and dissatisfaction. But it’s the associated health risks that often drive people to take action. A lot of the women who join my free 30-Day PCOS Diet Challenge do so for their families. They want to be healthy so they can take better care of their loved ones.

PCOS is a metabolic disorder. This means that women with PCOS have increased risks of type 2 diabetes, heart disease, and some forms of cancer [5].

But because it’s a metabolic disorder, this also means there’s a lot you can do about PCOS yourself. Even if they disagree on the details, almost all experts advise that diet and lifestyle interventions should be the first treatment prescribed for managing PCOS.

Summary

Women with PCOS have increased long-term health risks. But these risks can be reduced through diet and lifestyle interventions.

PCOS and Pregnancy

Between 70 and 80% of women with PCOS have trouble falling (or staying) pregnant [6, 7]. That’s because PCOS:

- Impairs ovulation and reduces egg quality [8-11].

- Makes the womb less receptive during implantation [12, 13].

- Increases the risk of miscarriage by 40-60% [14-16].

Being overweight is one of the main causes of these issues [10, 17-19]. Although infertility affects lean women with PCOS too. Somewhat ironically, this is good news. Because this is a problem that can be addressed through diet and lifestyle interventions. We’ve seen this in scientific studies [20]. It’s also something we witness daily within my PCOS community. Just take a look at these PCOS pregnancy success stories and learn more about getting pregnant with PCOS here.

Summary

PCOS makes it harder to have children. But a lot of this difficulty can be addressed through diet and lifestyle interventions.

PCOS and Body Weight

PCOS makes it hard to lose weight and easy to gain it [21, 22]. That’s why more than half of women with this syndrome are considered overweight [23].

Insulin resistance is the primary mechanism that causes PCOS weight gain. This is where your cells are less capable of processing glucose. Over time, insulin resistance causes higher rates of body fat accumulation [24-26].

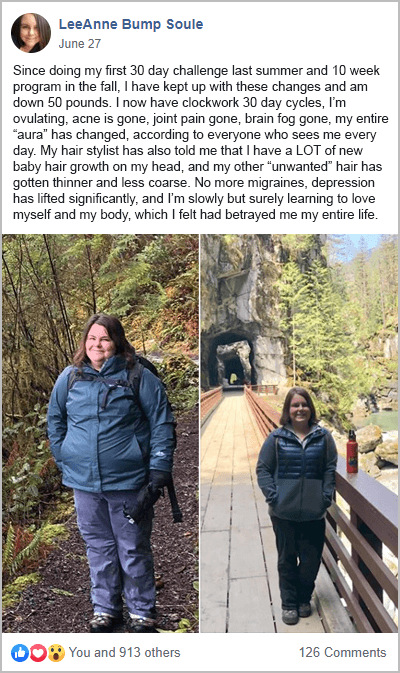

But like infertility, this is a problem that can be fixed with the right information and support. That’s what these PCOS weight loss success stories show. Switching to the right diet for PCOS can help you lose weight, even when all previous diets have failed you.

Learn how to lose weight with PCOS here.

Summary

Achieving and maintaining a healthy body weight is more difficult for women with PCOS. But this problem can be resolved with the right dietary interventions.

What Causes PCOS?

The causes of PCOS are complex. Some experts argue that the high prevalence of this syndrome, along with many other chronic illnesses, is a consequence of our modern environments [27].

Estimates suggest that approximately 70% of PCOS has a genetic basis [28]. But we also know that it’s triggered during gestation by imbalances in the womb [29-32]. Chemical or biological toxicant exposure, for example, plays an important role in fetal programming of PCOS [33, 34].

Your diet, lifestyle, and environment also drive the development of PCOS [35, 36]. Especially during your teens. The negative impact of an unhealthy diet and lifestyle on PCOS has been well-established in the scientific literature [37]. More specifically, an unhealthy gut microbiome can account for all three PCOS diagnostic criteria [13, 38].

But this isn’t all bad news. The fact that PCOS is made worse by a poor diet and lifestyle, and an unhappy gut, speaks to the reversibility of this syndrome.

Summary

PCOS has a strong genetic basis. But it appears to be caused by environmental factors, especially during gestation. A poor diet and lifestyle during childhood and adolescence make it more likely that you’ll develop PCOS as an adult.

How to Treat PCOS

Medical treatment of PCOS is largely restricted to treating the presenting symptoms.

Birth control is the most common treatment given to women with PCOS. That’s because this treatment strategy is to override your hormonal imbalances. But using birth control for PCOS is not without its risks. I explain more here.

Metformin is another common treatment for PCOS. That’s because metformin improves insulin sensitivity, which in turn, can help restore hormone balance. Metformin is prescribed to help with weight management and to lower the risk of developing diabetes. It’s also used to improve menstruation and to help treat PCOS infertility.

Unfortunately, the weight of scientific evidence does not support the use of metformin for these purposes. As explained in more detail here, since 2018, experts have recommended against the use of metformin as a PCOS treatment for “any indication”.

In my view, you’re much better off taking myo-inositol and/or berberine which work just as well.

Spironolactone is another medicine that is commonly used off-label for the treatment of PCOS acne, hair loss, and hirsutism. Spironolactone lowers androgen levels, which can help relieve PCOS symptoms. However, the FDA has put a black box warning on this medicine due to concerns that it may cause tumors.

Summary

Doctors have limited tools for treating PCOS. Pharmaceutical medications are often prescribed to help alleviate symptoms.

Diet & Lifestyle Changes

PCOS symptoms are predominantly caused by insulin resistance and chronic inflammation [37, 39-44]. This is great news for anyone wanting to treat PCOS naturally. That’s because both of these mechanisms can be dialed up or down by your diet and lifestyle.

The best diet for PCOS reduces inflammation and improves blood sugar regulation. Healing the gut is a core part of this process.

Download a free 3-Day PCOS meal plan here to see what this looks like in real life.

You can also take a bolder step forward by completing my free 30-Day PCOS Diet Challenge. During this event, you’ll join a supportive community of like-minded women. You’ll also receive meal plans, recipes, shopping lists, video lessons, and more.

There are also many dietary supplements and herbal medicines that can also relieve your symptoms. In many cases, these are just as effective as pharmaceutical solutions.

For example, I recommend that all of my clients consider supplementing with vitamin D and magnesium. That’s because the risk of inadequacy is high for these essential nutrients. But from a therapeutic perspective, myo-inositol is one of the most well-studied PCOS supplements. As explained here, myo-inositol is great for fertility and is an equally powerful substitute for metformin. Berberine also has pharmaceutical-level effects for the management of insulin resistance.

Summary

Diet and lifestyle changes are a powerful, evidence-based intervention for the treatment of PCOS. Nutritional supplements can also be useful for managing symptoms and enhancing results.

When to See a Doctor

If you suspect you may have PCOS, it’s best to see a doctor. Getting a formal diagnosis is helpful for managing your long-term health risks. Your doctor can also advise on your reproductive health. This is especially important if you intend to start a family in the future.

Summary

It’s best to consult with your doctor if you’re concerned you may have PCOS. They can provide a clinical diagnosis and help manage your treatment moving forward.

The Bottom Line

Common symptoms of PCOS include irregular periods, and challenges with your weight, skin, and hair. This syndrome has a significant impact on fertility. It also presents increased metabolic and cardiovascular health risks.

Medical treatments can relieve the symptoms of PCOS. But many women with this syndrome are able to manage their symptoms through diet and lifestyle interventions alone. Become one of these women today by joining my free 30-Day PCOS Diet Challenge here. Or download this free 3-Day meal plan to get started.

Author

As a Nutritionist, I’m continuing my mission to help women like you, beat PCOS. Evidence-based diet and lifestyle interventions helped me overcome five years of infertility. I fell pregnant naturally after multiple failed IVF cycles. Along the way, my other PCOS symptoms went away too. This experience taught me how to combine the latest science with a pragmatic approach to habit change. I’ve now helped thousands of other women achieve life-changing results, and I love for you to be the next PCOS success story. Learn more about me and what I do here.

References

1Christ, J.P. and M.I. Cedars, Current Guidelines for Diagnosing PCOS. Diagnostics (Basel), 2023. 13(6).

2Teede, H.J., et al., Recommendations from the international evidence-based guideline for the assessment and management of polycystic ovary syndrome. Hum Reprod, 2018. 33(9): p. 1602-1618.

3Clark, N.M., et al., Prevalence of Polycystic Ovary Syndrome Phenotypes Using Updated Criteria for Polycystic Ovarian Morphology: An Assessment of Over 100 Consecutive Women Self-reporting Features of Polycystic Ovary Syndrome. Reproductive Sciences, 2014. 21(8): p. 1034-1043.

4Sachdeva, G., et al., Comparison of the Different PCOS Phenotypes Based on Clinical Metabolic, and Hormonal Profile, and their Response to Clomiphene. Indian J Endocrinol Metab, 2019. 23(3): p. 326-331.

5Daniilidis, A. and K. Dinas, Long term health consequences of polycystic ovarian syndrome: a review analysis. Hippokratia, 2009. 13(2): p. 90-2.

6Melo, A.S., R.A. Ferriani, and P.A. Navarro, Treatment of infertility in women with polycystic ovary syndrome: approach to clinical practice. Clinics (Sao Paulo), 2015. 70(11): p. 765-9.

7Joham, A.E., et al., Prevalence of infertility and use of fertility treatment in women with polycystic ovary syndrome: data from a large community-based cohort study. J Womens Health (Larchmt), 2015. 24(4): p. 299-307.

8Patil, K., et al., Compromised Cumulus-Oocyte Complex Matrix Organization and Expansion in Women with PCOS. Reprod Sci, 2021.

9Chang, R.J. and H. Cook-Andersen, Disordered follicle development. Mol Cell Endocrinol, 2013. 373(1-2): p. 51-60.

10Palomba, S., J. Daolio, and G.B. La Sala, Oocyte Competence in Women with Polycystic Ovary Syndrome. Trends Endocrinol Metab, 2017. 28(3): p. 186-198.

11Patel, S.S. and B.R. Carr, Oocyte quality in adult polycystic ovary syndrome. Semin Reprod Med, 2008. 26(2): p. 196-203.

12Giudice, L.C., Endometrium in PCOS: Implantation and predisposition to endocrine CA. Best Pract Res Clin Endocrinol Metab, 2006. 20(2): p. 235-44.

13Shan, H., et al., Abnormal Endometrial Receptivity and Oxidative Stress in Polycystic Ovary Syndrome. Front Pharmacol, 2022. 13: p. 904942.

14Luo, L., et al., Early miscarriage rate in lean polycystic ovary syndrome women after euploid embryo transfer – a matched-pair study. Reprod Biomed Online, 2017. 35(5): p. 576-582.

15Sha, T., et al., A meta-analysis of pregnancy-related outcomes and complications in women with polycystic ovary syndrome undergoing IVF. Reprod Biomed Online, 2019. 39(2): p. 281-293.

16Matorras, R., et al., Polycystic ovarian syndrome and miscarriage in IVF: systematic revision of the literature and meta-analysis. Arch Gynecol Obstet, 2022.

17Schulte, M.M., J.H. Tsai, and K.H. Moley, Obesity and PCOS: the effect of metabolic derangements on endometrial receptivity at the time of implantation. Reprod Sci, 2015. 22(1): p. 6-14.

18Gonzalez, M.B., et al., Inflammatory markers in human follicular fluid correlate with lipid levels and Body Mass Index. J Reprod Immunol, 2018. 130: p. 25-29.

19Broughton, D.E. and K.H. Moley, Obesity and female infertility: potential mediators of obesity’s impact. Fertil Steril, 2017. 107(4): p. 840-847.

20Abdulkhalikova, D., et al., The Lifestyle Modifications and Endometrial Proteome Changes of Women With Polycystic Ovary Syndrome and Obesity. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne), 2022. 13: p. 888460.

21Sam, S., Obesity and Polycystic Ovary Syndrome. Obes Manag, 2007. 3(2): p. 69-73.

22Lim, S., et al., Barriers and facilitators to weight management in overweight and obese women living in Australia with PCOS: a qualitative study. BMC Endocr Disord, 2019. 19(1): p. 106.

23Deswal, R., et al., The Prevalence of Polycystic Ovary Syndrome: A Brief Systematic Review. J Hum Reprod Sci, 2020. 13(4): p. 261-271.

24Zeng, X., et al., Polycystic ovarian syndrome: Correlation between hyperandrogenism, insulin resistance and obesity. Clin Chim Acta, 2020. 502: p. 214-221.

25Bannigida, D.M., B.S. Nayak, and R. Vijayaraghavan, Insulin resistance and oxidative marker in women with PCOS. Arch Physiol Biochem, 2020. 126(2): p. 183-186.

26Petersen, M.C. and G.I. Shulman, Mechanisms of Insulin Action and Insulin Resistance. Physiol Rev, 2018. 98(4): p. 2133-2223.

27Naviaux, R.K., Perspective: Cell danger response Biology-The new science that connects environmental health with mitochondria and the rising tide of chronic illness. Mitochondrion, 2020. 51: p. 40-45.

28Vink, J.M., et al., Heritability of polycystic ovary syndrome in a Dutch twin-family study. J Clin Endocrinol Metab, 2006. 91(6): p. 2100-4.

29Tata, B., et al., Elevated prenatal anti-Mullerian hormone reprograms the fetus and induces polycystic ovary syndrome in adulthood. Nature Medicine, 2018. 24(6): p. 834-+.

30Filippou, P. and R. Homburg, Is foetal hyperexposure to androgens a cause of PCOS? Human Reproduction Update, 2017. 23(4): p. 421-432.

31Raperport, C. and R. Homburg, The Source of Polycystic Ovarian Syndrome. Clinical Medicine Insights-Reproductive Health, 2019. 13.

32Fenichel, P., et al., Which origin for polycystic ovaries syndrome: Genetic, environmental or both? Annales D Endocrinologie, 2017. 78(3): p. 176-185.

33Hewlett, M., et al., Prenatal Exposure to Endocrine Disruptors: A Developmental Etiology for Polycystic Ovary Syndrome. Reproductive Sciences, 2017. 24(1): p. 19-27.

34Akgul, S., et al., THE ROLE OF ENDOCRINE DISRUPTORS IN THE AETIOPATHOGENESIS OF ADOLESCENT POLYCYSTIC OVARY SYNDROME. Journal of Adolescent Health, 2019. 64(2): p. S128-S129.

35Puttabyatappa, M., R.C. Cardoso, and V. Padmanabhan, Effect of maternal PCOS and PCOS-like phenotype on the offspring’s health. Molecular and Cellular Endocrinology, 2016. 435(C): p. 29-39.

36Bremer, A.A., Polycystic Ovary Syndrome in the Pediatric Population. Metabolic Syndrome and Related Disorders, 2010. 8(5): p. 375-394.

37Barrea, L., et al., Source and amount of carbohydrate in the diet and inflammation in women with polycystic ovary syndrome. Nutr Res Rev, 2018. 31(2): p. 291-301.

38Tremellen, K. and K. Pearce, Dysbiosis of Gut Microbiota (DOGMA)–a novel theory for the development of Polycystic Ovarian Syndrome. Med Hypotheses, 2012. 79(1): p. 104-12.

39Carvalho, L.M.L., et al., Polycystic Ovary Syndrome as a systemic disease with multiple molecular pathways: a narrative review. Endocr Regul, 2018. 52(4): p. 208-221.

40González, F., Inflammation in Polycystic Ovary Syndrome: underpinning of insulin resistance and ovarian dysfunction. Steroids, 2012. 77(4): p. 300-5.

41González, F., et al., Hyperandrogenism sensitizes mononuclear cells to promote glucose-induced inflammation in lean reproductive-age women. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab, 2012. 302(3): p. E297-306.

42Popovic, M., G. Sartorius, and M. Christ-Crain, Chronic low-grade inflammation in polycystic ovary syndrome: is there a (patho)-physiological role for interleukin-1? Seminars in Immunopathology, 2019. 41(4): p. 447-459.

43Rudnicka, E., et al., Chronic Low Grade Inflammation in Pathogenesis of PCOS. Int J Mol Sci, 2021. 22(7).

44Wang, J., et al., Hyperandrogenemia and insulin resistance: The chief culprit of polycystic ovary syndrome. Life Sciences, 2019. 236.

As a Nutritionist, I’m continuing my mission to help women like you, beat PCOS. Evidence-based diet and lifestyle interventions helped me overcome five years of infertility. I fell pregnant naturally after multiple failed IVF cycles. Along the way, my other PCOS symptoms went away too. This experience taught me how to combine the latest science with a pragmatic approach to habit change. I’ve now helped thousands of other women achieve life-changing results, and I love for you to be the next PCOS success story. Learn more about me and what I do here.