PCOS acne isn’t a skin problem. That’s why most treatments reduce your bank balance faster than your pimples. They fail to address the underlying causes.

Here’s what you need to know about the true cause of PCOS acne and how to treat this problem. As you’ll discover, switching to a PCOS diet is essential. Get started today by downloading this free 3-Day PCOS meal plan. For more recipes and meal plans, you can also sign-up for my free 30-Day PCOS Diet Challenge. This program delivers video lessons and activities within a supportive online community.

The Cause of PCOS Acne

It used to be assumed that acne was caused by elevated androgens, like testosterone. This hypothesis is outdated and incorrect.

Acne is now understood to be an inflammatory disease [1-4].

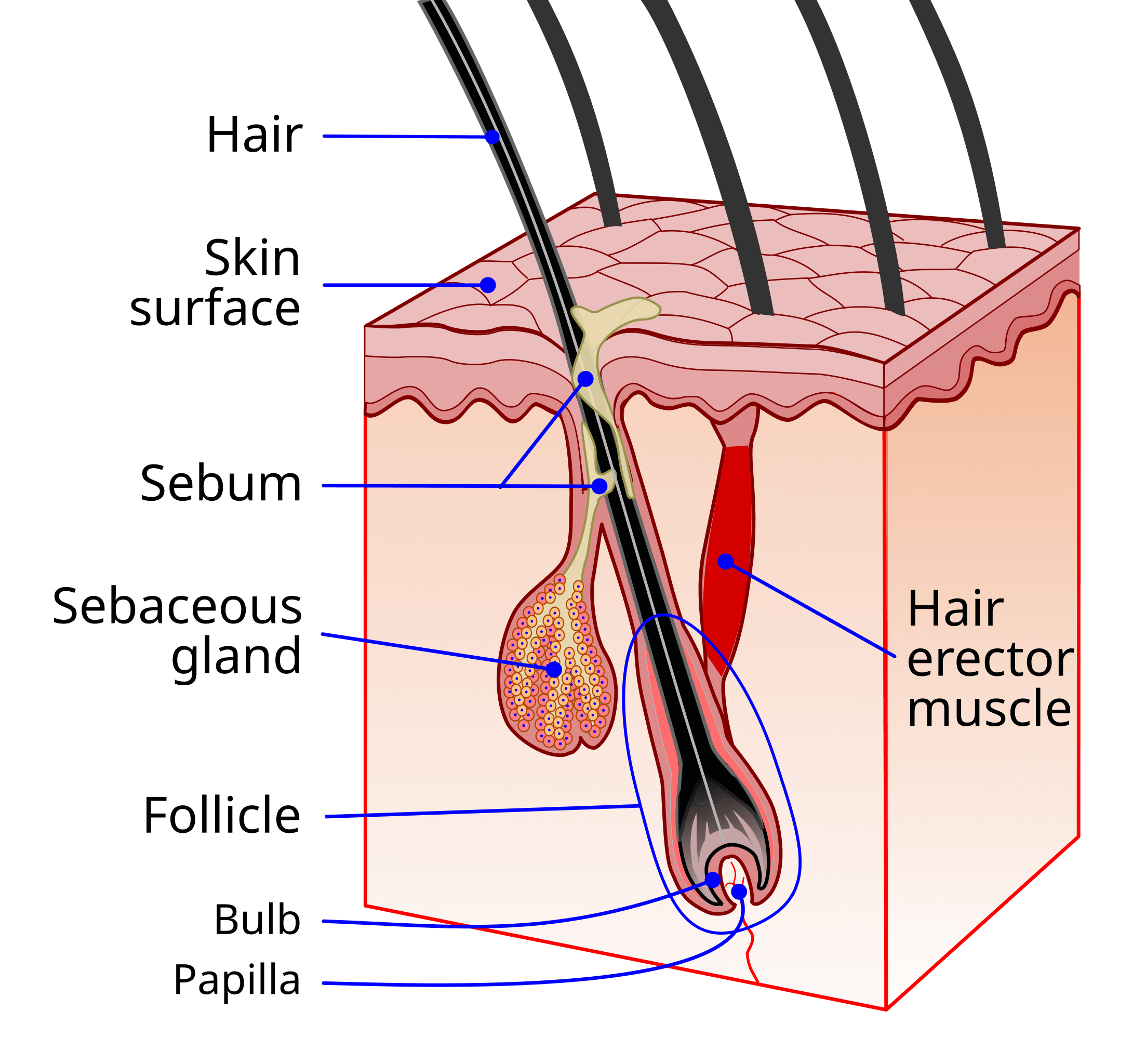

It occurs when inflammation in skin cells triggers two responses. The overproduction of keratin and changes in sebum composition. Keratin is a sticky skin protein. Sebum is an oily substance produced by tiny glands that empty into hair follicles.

The changes in keratin and sebum production clog pores and cause further inflammation. The immune system then produces puss in response. That’s how pimples and skin lesions form [5-8].

The buildup of sebum and keratin also provides the perfect breeding ground for acne bacteria. These bacteria help to rupture the pore wall. They can also cause more inflammation making the acne worse [5, 9, 10].

The process for acne formation is the same in women with PCOS. The big difference though is that we already have an issue with chronic inflammation. Inflammation is one of the underlying causes of all PCOS symptoms [11-15]. It’s this pre-existing problem with inflammation that makes acne a common symptom for many women with this syndrome.

There are many natural ways to reduce PCOS inflammation. Doing so can reduce symptoms. This includes acne, eczema, hirsutism, and hair loss. Reducing inflammation is how you lose weight with PCOS. It’s also key to getting pregnant with PCOS.

The treatment and prevention of PCOS acne is synonymous with the treatment of PCOS generally. Fixing PCOS resolves acne. Keep this in mind when considering the five PCOS acne treatments described below. The effectiveness of any intervention is a function of how well it reduces systemic inflammation.

1. Dietary Changes

Out of all acne treatments, a PCOS diet delivers the greatest return on investment. It’s the best way to reduce the underlying inflammation that causes PCOS. Not only does this treat acne. All other PCOS symptoms can be improved at the same time.

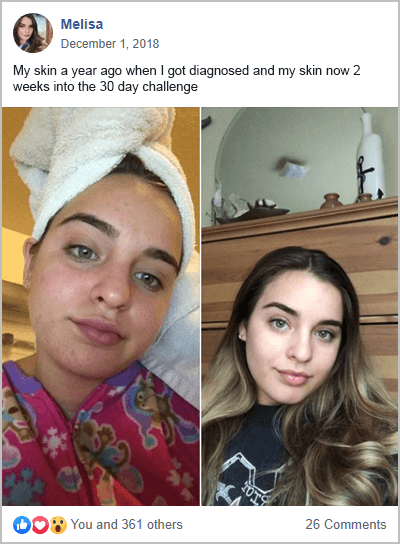

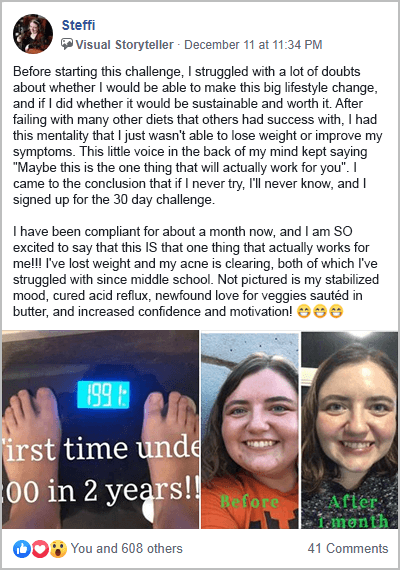

This can be seen in many of the success stories from my free 30-Day PCOS Diet Challenge. People often join this program because they’re fed up with ineffective treatments. It’s common for acne to be one of the first symptoms to clear.

There are three key aspects to a PCOS acne diet. Avoid foods that cause inflammation. Eat more foods that reduce inflammation. Eat in a way that improves insulin regulation.

I’ve identified seven foods to avoid with PCOS. Sugar is top of this list. But as I explain in my articles on gluten and dairy, these foods are also pro-inflammatory. Dairy, in particular, has been directly associated with acne [16, 17].

Consuming more foods that reduce inflammation is essentially about eating healthy. More than 25,000 nutrients have been identified that can only be found in plant foods. Many of these exert antioxidant and anti-inflammatory effects. This is why a good PCOS diet is rich in non-starchy vegetables. Many other whole foods can also reduce inflammation. Oily fish, avocado, nuts, seeds, and olive oil are obvious stand-outs.

Eating to improve insulin regulation is mission-critical. This is because an unhealthy diet that drives insulin resistance is another central feature of a PCOS diagnosis [18]. Insulin resistance is caused by inflammation in women with PCOS [12]. But insulin resistance also causes inflammation [19]. It’s been directly implicated in the pathogenesis of acne [20]. Improving insulin sensitivity is all about achieving tight control over blood glucose levels. I explain how to do this in my article, The Best Macros for PCOS. Studies have shown that a low-glycemic load diet reduces acne lesions [21, 22]. Eating more fiber is also important for improving insulin regulation [23, 24].

2. Acne Supplements

Many dietary supplements can help prevent and treat acne. Examine.com maintains a database of acne supplement studies. According to this database, zinc and vitamin B3 are the most well-supported acne supplements. There’s also growing interest in the use of probiotics [25].

Taking a PCOS-centric focus, any supplement that treats PCOS may also reduce PCOS acne.

Myo-inositol products like Ovasitol, for instance, are the closest thing to a PCOS supplement. Most studies on this supplement are about insulin sensitivity and ovarian function. But at least one study has shown that myo-inositol can decrease hirsutism and acne in PCOS women [26].

Because of its impact on inflammation and insulin, taking vitamin D for PCOS may also help with acne.

3. Lifestyle Solutions

As described above, both acne and PCOS are inflammatory processes. This means that other lifestyle interventions can also be an effective treatment. If something reduces inflammation, then it can reduce the severity of acne.

The most powerful evidence-based lifestyle changes are sleep, exercise, and stress reduction. I’ve described these at length in my article on natural treatments for PCOS.

Poor quality sleep is known to be a risk factor for both insulin resistance and inflammation [27-30]. This makes better sleep hygiene a simple way to treat PCOS and acne.

Studies show that both strength training and aerobic exercise improve outcomes for PCOS women [31-34]. At least 120 to 150 minutes per week of vigorous-intensity exercise is recommended [35, 36].

Reducing psychological stress is another way to take back control of your health and well-being. Stress is known to reliably increase the circulation of inflammatory markers. A meta-analysis of the effects of stress draws an association between, “life challenges and vulnerability to inflammatory disease [37].” Inflammatory diseases like PCOS and acne.

4. Pharmaceutical Solutions

Oral Contraceptives and Spironolactone

There are many pharmaceutical solutions to acne. Oral contraceptives treat PCOS acne by reducing androgen levels. This can also be achieved with anti-androgenic drugs like spironolactone. The use of these medications is based on the “old” idea that excess androgens start and perpetuate the acne inflammatory cascade [1]. As described above, we now know that inflammation precedes excess androgen production.

Metformin

Metformin also has a track record as an effective PCOS acne treatment [38, 39]. Like contraceptives and Spironolactone, Metformin reduces excess androgens.

Retinoid Treatments

Retinoid treatments are vitamin A derivatives. They can be administered either topically (Retin-A) or orally (Accutane). These prescription medicines are stronger than over-the-counter retinol products. Topical retinoids have anti-inflammatory effects. But the main way they reduce acne is by boosting the production of new skin cells. This pushes dead cells and excess oil out of blocked pores.

Accutane is sometimes considered “the nuclear option”. It’s the single most effective drug for treatment-resistant acne [40]. Accutane clears acne by permanently reducing skin oil production. It also reduces acne bacteria, prevents clogged pores, and reduces inflammation [41-45].

Antibiotics

Antibiotics help stop the growth of acne bacteria from the inside out [46]. They also have an anti-inflammatory effect [47, 48]. Antibiotics work for about half of people with acne [49]. They’re moderately effective but can only be used for 3 months or less. This is because your acne “gets used” to the treatment and becomes resistant over time [50, 51].

Important Warning

Caution is warranted before using any of the above pharmaceutical acne treatments. These treatments don’t treat the underlying cause of acne. In some cases, they can do more harm than good.

For example, in my article on PCOS and birth control, I explore the risks of hormonal contraceptives for treating PCOS. I explain the seven reasons not to take metformin for PCOS here. Accutane has potentially severe side effects and must not be used if there’s the possibility of falling pregnant.

Diet and lifestyle changes are a much safer approach. They have no adverse side effects and the benefits go well beyond treating acne. Making diet and lifestyle changes is how I cured my PCOS acne. Many other women from my free 30-Day PCOS Diet Challenge have done the same. Katy is a great example.

5. Skin Treatments

Many skin treatments can provide temporary relief from PCOS acne. The most common over-the-counter product ingredients include benzoyl peroxide, salicylic acid, and azelaic acid. Chemical peels, micro-needling, and laser therapy are also often used.

If you prefer more natural skin treatments, purified bee venom gel and tea tree oil may be your best bet. Studies have found that topical use of these ingredients has helped reduce acne lesions [52].

The biggest shortcoming with all skin treatments is that they only “work” while you’re using them. If you fail to address the underlying inflammation then these treatments provide limited benefit.

The Bottom Line

There are many ways to prevent and treat PCOS acne. Skin treatments and pharmaceutical drugs are the most common solutions. But these treatments have limited benefits. This is because they fail to address the underlying causes. The safety and side effects of these treatments also need to be considered.

PCOS and acne are both inflammation-driven processes. Inflammation can be addressed through diet, supplements, and lifestyle interventions. The efficacy of this approach has been well-demonstrated by participants from my free 30-Day PCOS Diet Challenge. Like me, many women have eliminated their acne through diet change alone. I want this to become a more universal phenomenon.

I hope you’ll join us soon.

Author

As a Nutritionist, I’m continuing my mission to help women like you, beat PCOS. Evidence-based diet and lifestyle interventions helped me overcome five years of infertility. I fell pregnant naturally after multiple failed IVF cycles. Along the way, my other PCOS symptoms went away too. This experience taught me how to combine the latest science with a pragmatic approach to habit change. I’ve now helped thousands of other women achieve life-changing results, and I love for you to be the next PCOS success story. Learn more about me and what I do here.

References

1Kircik, L.H., Advances in the Understanding of the Pathogenesis of Inflammatory Acne. J Drugs Dermatol, 2016. 15(1 Suppl 1): p. s7-10.

2Tanghetti, E.A., The role of inflammation in the pathology of acne. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol, 2013. 6(9): p. 27-35.

3Williams, H.C., R.P. Dellavalle, and S. Garner, Acne vulgaris. Lancet, 2012. 379(9813): p. 361-72.

4Zouboulis, C.C., E. Jourdan, and M. Picardo, Acne is an inflammatory disease and alterations of sebum composition initiate acne lesions. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol, 2014. 28(5): p. 527-32.

5Kistowska, M., et al., IL-1β drives inflammatory responses to propionibacterium acnes in vitro and in vivo. J Invest Dermatol, 2014. 134(3): p. 677-685.

6Li, Z.J., et al., Propionibacterium acnes activates the NLRP3 inflammasome in human sebocytes. J Invest Dermatol, 2014. 134(11): p. 2747-2756.

7Selway, J.L., et al., Toll-like receptor 2 activation and comedogenesis: implications for the pathogenesis of acne. BMC Dermatol, 2013. 13: p. 10.

8Thiboutot, D.M., Inflammasome activation by Propionibacterium acnes: the story of IL-1 in acne continues to unfold. J Invest Dermatol, 2014. 134(3): p. 595-597.

9Contassot, E. and L.E. French, New insights into acne pathogenesis: propionibacterium acnes activates the inflammasome. J Invest Dermatol, 2014. 134(2): p. 310-313.

10Toyoda, M. and M. Morohashi, Pathogenesis of acne. Med Electron Microsc, 2001. 34(1): p. 29-40.

11Carvalho, L.M.L., et al., Polycystic Ovary Syndrome as a systemic disease with multiple molecular pathways: a narrative review. Endocr Regul, 2018. 52(4): p. 208-221.

12González, F., Inflammation in Polycystic Ovary Syndrome: underpinning of insulin resistance and ovarian dysfunction. Steroids, 2012. 77(4): p. 300-5.

13Popovic, M., G. Sartorius, and M. Christ-Crain, Chronic low-grade inflammation in polycystic ovary syndrome: is there a (patho)-physiological role for interleukin-1? Seminars in Immunopathology, 2019. 41(4): p. 447-459.

14Rostamtabar, M., et al., Pathophysiological roles of chronic low-grade inflammation mediators in polycystic ovary syndrome. J Cell Physiol, 2021. 236(2): p. 824-838.

15Rudnicka, E., et al., Chronic Low Grade Inflammation in Pathogenesis of PCOS. Int J Mol Sci, 2021. 22(7).

16Juhl, C.R., et al., Dairy Intake and Acne Vulgaris: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of 78,529 Children, Adolescents, and Young Adults. Nutrients, 2018. 10(8).

17Dai, R., et al., The effect of milk consumption on acne: a meta-analysis of observational studies. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol, 2018. 32(12): p. 2244-2253.

18Barrea, L., et al., Source and amount of carbohydrate in the diet and inflammation in women with polycystic ovary syndrome. Nutr Res Rev, 2018. 31(2): p. 291-301.

19Shimobayashi, M., et al., Insulin resistance causes inflammation in adipose tissue. J Clin Invest, 2018. 128(4): p. 1538-1550.

20Kumari, R. and D.M. Thappa, Role of insulin resistance and diet in acne. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol, 2013. 79(3): p. 291-9.

21Kwon, H.H., et al., Clinical and histological effect of a low glycaemic load diet in treatment of acne vulgaris in Korean patients: a randomized, controlled trial. Acta Derm Venereol, 2012. 92(3): p. 241-6.

22Smith, R.N., et al., A low-glycemic-load diet improves symptoms in acne vulgaris patients: a randomized controlled trial. Am J Clin Nutr, 2007. 86(1): p. 107-15.

23Cutler, D.A., S.M. Pride, and A.P. Cheung, Low intakes of dietary fiber and magnesium are associated with insulin resistance and hyperandrogenism in polycystic ovary syndrome: A cohort study. Food Sci Nutr, 2019. 7(4): p. 1426-1437.

24Weickert, M.O. and A.F.H. Pfeiffer, Impact of Dietary Fiber Consumption on Insulin Resistance and the Prevention of Type 2 Diabetes. J Nutr, 2018. 148(1): p. 7-12.

25Goodarzi, A., et al., The potential of probiotics for treating acne vulgaris: A review of literature on acne and microbiota. Dermatol Ther, 2020. 33(3): p. e13279.

26Zacchè, M.M., et al., Efficacy of myo-inositol in the treatment of cutaneous disorders in young women with polycystic ovary syndrome. Gynecol Endocrinol, 2009. 25(8): p. 508-13.

27Van Cauter, E., Sleep disturbances and insulin resistance. Diabet Med, 2011. 28(12): p. 1455-62.

28Nedeltcheva, A.V., et al., Exposure to recurrent sleep restriction in the setting of high caloric intake and physical inactivity results in increased insulin resistance and reduced glucose tolerance. J Clin Endocrinol Metab, 2009. 94(9): p. 3242-50.

29Tasali, E., et al., Impact of obstructive sleep apnea on insulin resistance and glucose tolerance in women with polycystic ovary syndrome. J Clin Endocrinol Metab, 2008. 93(10): p. 3878-84.

30Irwin, M.R., R. Olmstead, and J.E. Carroll, Sleep Disturbance, Sleep Duration, and Inflammation: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Cohort Studies and Experimental Sleep Deprivation. Biol Psychiatry, 2016. 80(1): p. 40-52.

31Cheema, B.S., L. Vizza, and S. Swaraj, Progressive resistance training in polycystic ovary syndrome: can pumping iron improve clinical outcomes? Sports Med, 2014. 44(9): p. 1197-207.

32Almenning, I., et al., Effects of High Intensity Interval Training and Strength Training on Metabolic, Cardiovascular and Hormonal Outcomes in Women with Polycystic Ovary Syndrome: A Pilot Study. PLoS One, 2015. 10(9): p. e0138793.

33Covington, J.D., et al., Higher circulating leukocytes in women with PCOS is reversed by aerobic exercise. Biochimie, 2016. 124: p. 27-33.

34Shele, G., J. Genkil, and D. Speelman, A Systematic Review of the Effects of Exercise on Hormones in Women with Polycystic Ovary Syndrome. J Funct Morphol Kinesiol, 2020. 5(2).

35Patten, R.K., et al., Exercise Interventions in Polycystic Ovary Syndrome: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Front Physiol, 2020. 11: p. 606.

36Woodward, A., M. Klonizakis, and D. Broom, Exercise and Polycystic Ovary Syndrome. Adv Exp Med Biol, 2020. 1228: p. 123-136.

37Marsland, A.L., et al., The effects of acute psychological stress on circulating and stimulated inflammatory markers: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Brain Behav Immun, 2017. 64: p. 208-219.

38Sharma, S., et al., Efficacy of Metformin in the Treatment of Acne in Women with Polycystic Ovarian Syndrome: A Newer Approach to Acne Therapy. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol, 2019. 12(5): p. 34-38.

39Yen, H., et al., Metformin Therapy for Acne in Patients with Polycystic Ovary Syndrome: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Am J Clin Dermatol, 2021. 22(1): p. 11-23.

40Demirci Saadet, E., Investigation of relapse rate and factors affecting relapse after oral isotretinoin treatment in patients with acne vulgaris. Dermatol Ther, 2021. 34(6): p. e15109.

41Demircay, Z., S. Kus, and H. Sur, Predictive factors for acne flare during isotretinoin treatment. Eur J Dermatol, 2008. 18(4): p. 452-6.

42Ellis, C.N. and K.J. Krach, Uses and complications of isotretinoin therapy. J Am Acad Dermatol, 2001. 45(5): p. S150-7.

43Mandekou-Lefaki, I., et al., Low-dose schema of isotretinoin in acne vulgaris. Int J Clin Pharmacol Res, 2003. 23(2-3): p. 41-6.

44Nelson, A.M., et al., 13-cis Retinoic acid induces apoptosis and cell cycle arrest in human SEB-1 sebocytes. J Invest Dermatol, 2006. 126(10): p. 2178-89.

45Plewig, G., et al., Low dose isotretinoin combined with tretinoin is effective to correct abnormalities of acne. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges, 2004. 2(1): p. 31-45.

46Kurokawa, I., S. Nishijima, and S. Kawabata, Antimicrobial susceptibility of Propionibacterium acnes isolated from acne vulgaris. Eur J Dermatol, 1999. 9(1): p. 25-8.

47Mays, R.M., et al., New antibiotic therapies for acne and rosacea. Dermatol Ther, 2012. 25(1): p. 23-37.

48Perret, L.J. and C.P. Tait, Non-antibiotic properties of tetracyclines and their clinical application in dermatology. Australas J Dermatol, 2014. 55(2): p. 111-8.

49Ozolins, M., et al., Randomised controlled multiple treatment comparison to provide a cost-effectiveness rationale for the selection of antimicrobial therapy in acne. Health Technol Assess, 2005. 9(1): p. iii-212.

50Eady, A.E., J.H. Cove, and A.M. Layton, Is antibiotic resistance in cutaneous propionibacteria clinically relevant? : implications of resistance for acne patients and prescribers. Am J Clin Dermatol, 2003. 4(12): p. 813-31.

51Leyden, J. and S. Levy, The development of antibiotic resistance in Propionibacterium acnes. Cutis, 2001. 67(2 Suppl): p. 21-4.

52Cao, H., et al., Complementary therapies for acne vulgaris. Cochrane Database Syst Rev, 2015. 1: p. Cd009436.

As a Nutritionist, I’m continuing my mission to help women like you, beat PCOS. Evidence-based diet and lifestyle interventions helped me overcome five years of infertility. I fell pregnant naturally after multiple failed IVF cycles. Along the way, my other PCOS symptoms went away too. This experience taught me how to combine the latest science with a pragmatic approach to habit change. I’ve now helped thousands of other women achieve life-changing results, and I love for you to be the next PCOS success story. Learn more about me and what I do here.