Key Takeaways

Polycystic ovary syndrome, or PCOS, is one of the most common causes of female infertility.

PCOS impairs ovulation [1, 2], reduces egg quality [3, 4], and makes the womb less receptive during implantation [5, 6]. Women with PCOS also tend to experience higher rates of miscarriage as a result of this syndrome [7].

Yet despite these disadvantages, it is still possible to get pregnant. It just requires a little more work.

I’ve done it, and so have thousands of other women, after completing my free 30-Day PCOS Diet Challenge.

If you want to know how to get pregnant with PCOS, then here are 11 expert-approved tips. The interventions covered range from a healthy diet to advanced reproductive technology.

1. Measure Your Metabolic Health

No one should ever feel ashamed of their weight, especially since PCOS can cause rapid weight gain. But the harsh reality is that both obesity and insulin resistance reduce fertility in PCOS women [8-10]. Because of this, your metabolic health can tell you a lot about your reproductive potential.

Obesity has many negative effects on reproductive processes. This includes reduced egg quality [11], disrupted embryo development, and impaired receptivity of the uterus [12]. For overweight women with PCOS, reducing body fat is one of the best ways to improve fertility and pregnancy outcomes [13]. Even modest weight loss of 5-10% can help [14-17] (see how to lose weight with PCOS here).

Insulin resistance is one of the primary causes of both weight gain and infertility in women with PCOS [18, 19]. This is a condition where your body becomes less sensitive to the hormone insulin. Lower insulin sensitivity causes elevated blood sugar levels. This causes body fat accumulation. But it also raises androgens, a.k.a. “male hormones.” This has a huge impact on your reproductive health. Physicians will often use fasting plasma glucose and A1C as indicators of insulin sensitivity. Monitoring these biomarkers over time can show improvements in your fertility.

Overweight women are often insulin resistant. But this diagnosis is often missed in normal-weight women with PCOS. Excess stomach fat is a common sign of insulin resistance in otherwise lean women. Having a waist-to-hip ratio higher than 0.85 is also used to assess this problem.

Hanna is a textbook case study of a lean woman with PCOS. She once suffered from insulin resistance and infertility. After realizing she had insulin resistance, Hanna made significant changes to her diet and lifestyle. By doing so, she was able to fall pregnant within a few months.

This was also my own experience after transforming my diet. Following over four years of failed fertility treatments, I was able to regulate my cycle and fall pregnant naturally.

2. Eat a PCOS-Friendly Diet

Scientists say that an unhealthy diet forms part of a “deadly quartet” of PCOS risk factors [20]. Together with insulin resistance, elevated androgen levels, and low-grade inflammation, high carbohydrate consumption causes PCOS infertility.

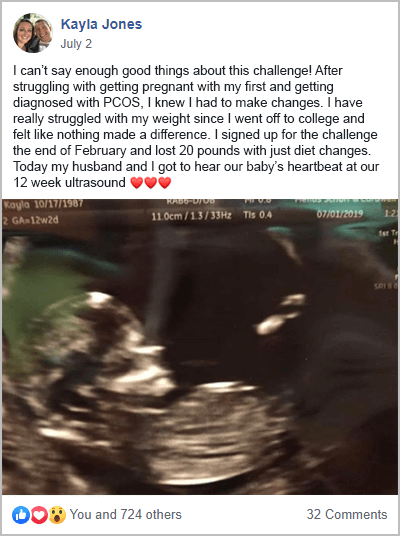

This is why a PCOS diet is one of the best fertility treatments. It’s not just about achieving a healthy weight. Dietary changes are often all that’s required to get pregnant too. The right diet improves insulin sensitivity and reduces inflammation. It fights all of the factors that reduce fertility in PCOS women. This can also improve other PCOS symptoms like unwanted hair, acne, anxiety, and depression. The best thing about eating for fertility though is that you can do it alongside any other treatment.

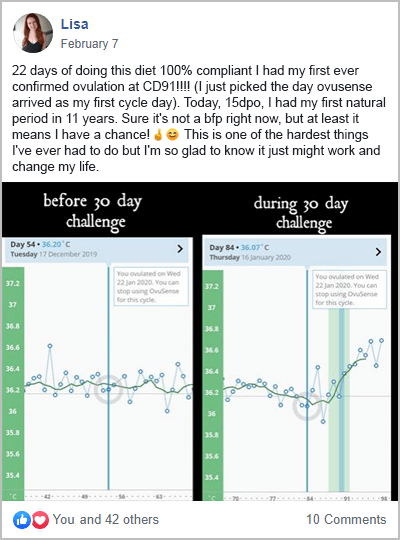

This was certainly Jamie’s experience. After participating in my free 30-Day PCOS Diet Challenge, Jamie lost weight, regulated her cycle, and soon fell pregnant.

If you want to test things out before making a 30-day commitment, this free 3-Day Meal Plan is a great place to start.

3. Consider Supplements

Certain minerals and vitamins can help with fertility. As explained in my article Vitamin D for PCOS, vitamin D supplementation is often warranted in women with PCOS. Vitamin D status impacts both fertility and pregnancy through a range of mechanisms [51-56]. Women with PCOS are also more likely to be deficient in this important nutrient. Methylated folate and iron are also among the most important supplements when trying to conceive.

Others worth considering include:

- Vitamins A, C, E, and K

- Various B vitamins, especially B6 and B12

- Calcium, iodine, magnesium, zinc, selenium, copper, and chromium

Prenatal vitamins aside, when it comes to fertility, myo-inositol is one of the most promising candidates for women with PCOS. This natural, vitamin-like sugar has a notable effect on fertility.

For women with PCOS, myo-inositol can improve ovarian function [21] and egg quality [22, 23]. During IVF trials, myo-inositol has increased the yield of mature eggs [24]. It’s improved pregnancy rates [25, 26] and reduced the risk of ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome [23]. Other studies have found that myo-inositol is better than birth control at regulating ovarian function [27]. It may also be better than metformin for boosting pregnancy rates [28].

Learn more about inositol for PCOS and fertility here.

4. Exercise Regularly

Exercise is a core component of any healthy lifestyle. It’s long been used to help people lose weight. But there’s also strong scientific evidence showing that it’s good for fertility. In overweight women with PCOS, exercise can lead to the resumption of ovulation [29]. This effect is independent of changes to your diet. Losing weight from exercise helps. But improvements in insulin sensitivity are the pivotal factor [30].

Both resistance (strength) training and aerobic activity are effective PCOS treatments [31-33]. This suggests that almost any kind of exercise is likely to be good for improving fertility.

5. Manage Your Stress

While it’s a cliché, stress can indeed play a significant role in preventing pregnancy in women with PCOS.

Studies have shown that women with PCOS produce unusually high levels of cortisol when stressed [34]. his reduces our capacity to cope. It also promotes insulin resistance and causes fat to accumulate on our stomachs and thighs [35, 36].

In a first-of-its-kind trial, US researchers found a two-fold increased risk of infertility in women that had the highest stress levels compared to those who were the least stressed [37]. This was a high-quality analysis that controlled for many confounding factors. This included age, race, income, alcohol, caffeine, and cigarette use.

Mindfulness meditation is one of the best direct stress-management tools. Similar practices like guided relaxation exercises and cognitive behavioral therapy are also helpful. Physical activity is another powerful way to reduce anxiousness [38].

Other, less direct stress management practices can help too. Referred to as “self-care” (for want of a better term), anything that helps you relax or let go of your stress can have a small but real effect.

6. Track Your Cycle

Getting pregnant is all about timing which is why tracking your menstrual cycle is so important. By monitoring changes in your basal body temperature and cervical mucus, you can know when you’re at your most fertile. Ovulation predictor kits can also be a valuable addition to your preconception toolkit.

Cycle tracking can be difficult for women with PCOS because they have irregular periods or they don’t ovulate. But a PCOS diet and other positive lifestyle changes can overcome these issues. Once your period is more regular, ovulation is more predictable.

7. Seek Fertility Treatment When Needed

For young women with PCOS, diet and lifestyle changes are often all that’s needed to restart ovulation. But these natural treatments can take between a couple of months to more than a year to work. If time is of the essence, then seeing a fertility specialist may be a good idea.

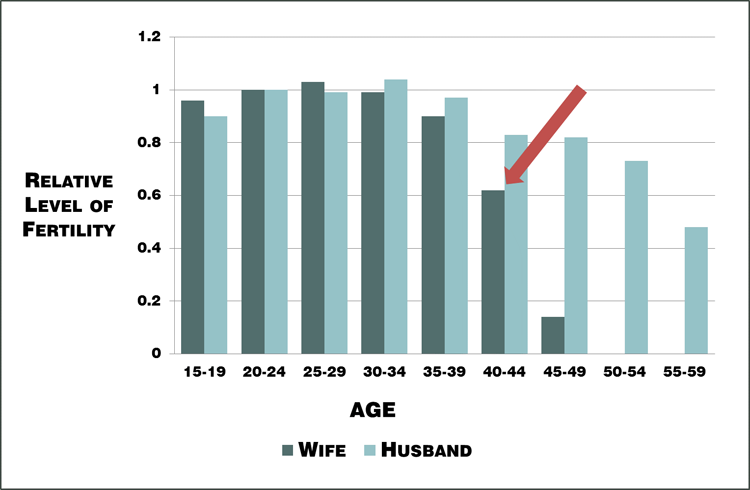

Besides male factor infertility, for women with PCOS, age is the key variable when deciding to advance to fertility treatments. Many fertility medications can help you get pregnant faster than you otherwise might.

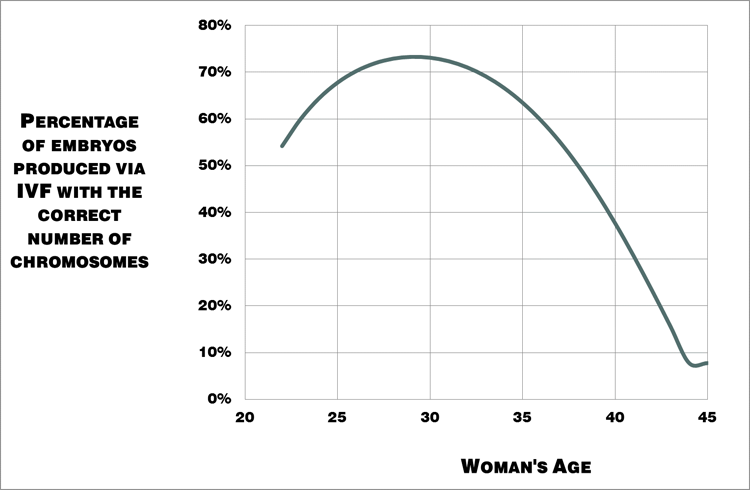

As the figure below shows, egg quality peaks in your late twenties and then declines rapidly after your mid-thirties. This has a direct effect on your chances of getting pregnant.

Figure 1. Percentage of embryos produced by women that have the correct number of chromosomes i.e. “good quality” eggs [39].

What this means for our “natural” fertility is that for the average woman, things start to get difficult once you hit 40.

Knowing that fertility treatments can also take time, it’s important to consider how long you’ll try on your own, before seeking help.

As you enter your mid to late 40s, using donor eggs will greatly improve your chances of success. For younger women though, this shouldn’t be needed unless surgical treatments of PCOS have reduced ovarian reserves [50].

Figure 2. Changes in relative “natural” fertility rates with age from historical population data [40].

8. Skip Metformin & Birth Control

When seeking fertility treatment, it’s as important to know what not to do as it is to know which treatments are best. Metformin is a great example of this.

Metformin is still used for infertility in women with polycystic ovary syndrom. Yet, it’s one of the least effective fertility drugs. Older studies show that metformin improves menstrual frequency, ovulation, and clinical pregnancy rates. But more recent reviews of the evidence are less supportive of this approach.

A 2019 systematic review challenged the idea that metformin increases live-birth rates. The strength of the effect was found to be small, and the quality of the evidence was low. Gastrointestinal side effects from this medication are significant though [41].

There are simply better alternatives to metformin for fertility.

Even the Endocrine Society Clinical Practice Guidelines state that “…metformin is beneficial for improving menstrual irregularities, but it has limited or no benefit in treating hirsutism, acne, or infertility” [42].

Learn more about metformin for PCOS here.

Another outdated practice is the use of hormonal birth control as a short-term PCOS preconception treatment. The idea here is that the pill suppresses the overproduction of androgens. In theory, this should then also kick-start ovulation once discontinued.

The problem with this approach is that it may do more harm than good. Preconception birth control has no benefit to your chances of ovulation. It can worsen metabolic health and may be detrimental to your fertility [43, 44]. See my PCOS birth control article for nine reasons to avoid this treatment.

9. Start with Clomid and/or Letrozole

When you need more help beyond diet and lifestyle changes, ovulation induction drugs are the obvious next step. Clomid and letrozole are the first-line therapies recommended by the World Health Organization [45]. Clomid has traditionally been the go-to first treatment. But many experts now believe that doctors should skip this step and head straight for letrozole instead. This is because letrozole results in better outcomes for women with PCOS [46-48].

Interestingly, this recommendation may soon be further updated. A randomized control trial found that clomid and letrozole used together were better than letrozole on its own [49].

In Karima’s case, Clomid + dietary change was the combination that worked for her. It was only after doubling down on the foods to avoid with PCOS that she fell pregnant on her seventh cycle.

10. Advance to Gonadotropins

If you don’t get pregnant with Clomid or letrozole, most fertility specialists will recommend injectable gonadotropins. These are used either with timed intercourse, intrauterine insemination (IUI), or in-vitro fertilization (IVF).

There are two active ingredients used in most gonadotropin products. Follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH), luteinizing hormone (LH), or a combination of the two. This includes Gonal-F, Follistim, Ovidrel, Bravelle, and Menopur. Gonadotropins can be used either on their own or in combination with oral fertility treatments like letrozole (Femara).

The biggest hazard with gonadotropins is their potential to overstimulate the ovary. This can cause ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome (OHSS). IVF egg collection is when the most gonadotropins are used, increasing the chances of OHSS. Studies show that myo-inositol can mitigate this risk [23]. But it remains important to establish the lowest effective gonadotropin dose required.

11. Add in IUI or IVF if Needed

Intrauterine insemination (IUI) is a type of artificial insemination that’s used to treat infertility. Sperm is first washed and concentrated. It’s then placed into the uterus with the hope that it’ll swim up into the fallopian tube to fertilize a waiting egg. This can be done with a “normal” cycle or after ovulation induction.

IUI is a limited procedure that still relies on the sperm and egg to do a lot of the “work.” By comparison, during in-vitro fertilization (IVF), every step of the process is controlled and monitored.

IVF starts with ovulation induction. But unlike natural conception or IUI, IVF uses a lot more gonadotropins. The goal is to mature and collect 12 – 20 eggs for fertilization in the lab.

Fertilization can occur by introducing the sperm into the same petri dish as the egg. Alternatively, one lucky sperm can be injected into the egg. This process is known as intracytoplasmic sperm injection (ICSI). ICSI is an optional technology. It increases fertilization rates and helps overcome male infertility.

Once the eggs are fertilized, they’re then grown for a few days under controlled lab conditions. After they’ve matured, these fertilized embryos can be placed back into the uterus as a “fresh embryo transfer.” They can also be cryogenically preserved for later use.

Somewhat ironically, women with PCOS may have an advantage over other women when it comes to IVF. This may be because PCOS women have higher ovarian reserve than age-matched controls. A higher ovarian reserve produces more embryos during IVF. This allows for more cycles which leads to better cumulative birth rates [57, 58].

In non-PCOS women, success rates go down significantly with age. But a 2011 study found that birth rates held stable between 22 and 41 years old in IVF patients with PCOS [59]. A similar study found that peak fertility was maintained until 38 years of age using IVF [60]. Others have found that PCOS women over 40 years have comparable success rates to those aged 35 to 40.

Just when you thought that it was all bad news!

The Bottom Line

Women with PCOS face a lot of extra obstacles when it comes to starting and growing their families. But that doesn’t mean it’s impossible with PCOS. You just need to work harder at it.

Diet and lifestyle changes can address the underlying root causes of PCOS. If required, assisted reproductive technologies also have outstanding success rates.

Whichever path you choose to go down, if you’re trying to conceive with PCOS, make sure to include diet and lifestyle changes as a core part of your fertility plan. You can get started today with this free 3-Day Meal Plan. Or sign-up for my free 30-Day PCOS Diet Challenge.

Author

As a Nutritionist, I’m continuing my mission to help women like you, beat PCOS. Evidence-based diet and lifestyle interventions helped me overcome five years of infertility. I fell pregnant naturally after multiple failed IVF cycles. Along the way, my other PCOS symptoms went away too. This experience taught me how to combine the latest science with a pragmatic approach to habit change. I’ve now helped thousands of other women achieve life-changing results, and I love for you to be the next PCOS success story. Learn more about me and what I do here.

Co-Authors

This blog post has been critically reviewed to ensure accurate interpretation and presentation of the scientific literature by Dr. Jessica A McCoy, Ph.D. Dr McCoy has a master’s degree in cellular and molecular biology, and a doctorate in reproductive biology and environmental health. She currently serves as a University professor at the College of Charleston, South Carolina.

This blog post has also been medically reviewed and approved by Dr. Sarah Lee, M.D. Dr. Lee is a board-certified Physician practicing with Intermountain Healthcare in Utah. She obtained a Bachelor of Science in Biology from the University of Texas at Austin before earning her Doctor of Medicine from UT Health San Antonio.

References

1Patil, K., et al., Compromised Cumulus-Oocyte Complex Matrix Organization and Expansion in Women with PCOS. Reprod Sci, 2021.

2Chang, R.J. and H. Cook-Andersen, Disordered follicle development. Mol Cell Endocrinol, 2013. 373(1-2): p. 51-60.

3Palomba, S., J. Daolio, and G.B. La Sala, Oocyte Competence in Women with Polycystic Ovary Syndrome. Trends Endocrinol Metab, 2017. 28(3): p. 186-198.

4Patel, S.S. and B.R. Carr, Oocyte quality in adult polycystic ovary syndrome. Semin Reprod Med, 2008. 26(2): p. 196-203.

5Giudice, L.C., Endometrium in PCOS: Implantation and predisposition to endocrine CA. Best Pract Res Clin Endocrinol Metab, 2006. 20(2): p. 235-44.

6Schulte, M.M., J.H. Tsai, and K.H. Moley, Obesity and PCOS: the effect of metabolic derangements on endometrial receptivity at the time of implantation. Reprod Sci, 2015. 22(1): p. 6-14.

7Luo, L., et al., Early miscarriage rate in lean polycystic ovary syndrome women after euploid embryo transfer – a matched-pair study. Reprod Biomed Online, 2017. 35(5): p. 576-582.

8Silvestris, E., et al., Obesity as disruptor of the female fertility. Reprod Biol Endocrinol, 2018. 16(1): p. 22.

9Al-Jefout, M., N. Alnawaiseh, and A. Al-Qtaitat, Insulin resistance and obesity among infertile women with different polycystic ovary syndrome phenotypes. Sci Rep, 2017. 7(1): p. 5339.

10He, F.F. and Y.M. Li, Role of gut microbiota in the development of insulin resistance and the mechanism underlying polycystic ovary syndrome: a review. J Ovarian Res, 2020. 13(1): p. 73.

11Snider, A.P. and J.R. Wood, Obesity induces ovarian inflammation and reduces oocyte quality. Reproduction, 2019. 158(3): p. R79-r90.

12Broughton, D.E. and K.H. Moley, Obesity and female infertility: potential mediators of obesity’s impact. Fertil Steril, 2017. 107(4): p. 840-847.

13Cena, H., L. Chiovato, and R.E. Nappi, Obesity, Polycystic Ovary Syndrome, and Infertility: A New Avenue for GLP-1 Receptor Agonists. J Clin Endocrinol Metab, 2020. 105(8): p. e2695-709.

14Thomson, R.L., et al., The effect of a hypocaloric diet with and without exercise training on body composition, cardiometabolic risk profile, and reproductive function in overweight and obese women with polycystic ovary syndrome. J Clin Endocrinol Metab, 2008. 93(9): p. 3373-80.

15Stamets, K., et al., A randomized trial of the effects of two types of short-term hypocaloric diets on weight loss in women with polycystic ovary syndrome. Fertil Steril, 2004. 81(3): p. 630-7.

16Tolino, A., et al., Evaluation of ovarian functionality after a dietary treatment in obese women with polycystic ovary syndrome. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol, 2005. 119(1): p. 87-93.

17Kuchenbecker, W.K., et al., In women with polycystic ovary syndrome and obesity, loss of intra-abdominal fat is associated with resumption of ovulation. Hum Reprod, 2011. 26(9): p. 2505-12.

18Marshall, J.C. and A. Dunaif, Should all women with PCOS be treated for insulin resistance? Fertil Steril, 2012. 97(1): p. 18-22.

19Wang, J., et al., Hyperandrogenemia and insulin resistance: The chief culprit of polycystic ovary syndrome. Life Sciences, 2019. 236.

20Barrea, L., et al., Source and amount of carbohydrate in the diet and inflammation in women with polycystic ovary syndrome. Nutr Res Rev, 2018. 31(2): p. 291-301.

21Gerli, S., et al., Randomized, double blind placebo-controlled trial: effects of myo-inositol on ovarian function and metabolic factors in women with PCOS. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci, 2007. 11(5): p. 347-54.

22Ciotta, L., et al., Effects of myo-inositol supplementation on oocyte’s quality in PCOS patients: a double blind trial. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci, 2011. 15(5): p. 509-14.

23Papaleo, E., et al., Myo-inositol may improve oocyte quality in intracytoplasmic sperm injection cycles. A prospective, controlled, randomized trial. Fertil Steril, 2009. 91(5): p. 1750-4.

24Garg, D. and R. Tal, Inositol Treatment and ART Outcomes in Women with PCOS. Int J Endocrinol, 2016. 2016: p. 1979654.

25Zheng, X., et al., Inositol supplement improves clinical pregnancy rate in infertile women undergoing ovulation induction for ICSI or IVF-ET. Medicine (Baltimore), 2017. 96(49): p. e8842.

26Artini, P.G., et al., Endocrine and clinical effects of myo-inositol administration in polycystic ovary syndrome. A randomized study. Gynecol Endocrinol, 2013. 29(4): p. 375-9.

27Ozay, A.C., et al., Different Effects of Myoinositol plus Folic Acid versus Combined Oral Treatment on Androgen Levels in PCOS Women. Int J Endocrinol, 2016. 2016: p. 3206872.

28Raffone, E., P. Rizzo, and V. Benedetto, Insulin sensitiser agents alone and in co-treatment with r-FSH for ovulation induction in PCOS women. Gynecol Endocrinol, 2010. 26(4): p. 275-80.

29Hakimi, O. and L.C. Cameron, Effect of Exercise on Ovulation: A Systematic Review. Sports Med, 2017. 47(8): p. 1555-1567.

30Palomba, S., et al., Structured exercise training programme versus hypocaloric hyperproteic diet in obese polycystic ovary syndrome patients with anovulatory infertility: a 24-week pilot study. Hum Reprod, 2008. 23(3): p. 642-50.

31Covington, J.D., et al., Higher circulating leukocytes in women with PCOS is reversed by aerobic exercise. Biochimie, 2016. 124: p. 27-33.

32Almenning, I., et al., Effects of High Intensity Interval Training and Strength Training on Metabolic, Cardiovascular and Hormonal Outcomes in Women with Polycystic Ovary Syndrome: A Pilot Study. PLoS One, 2015. 10(9): p. e0138793.

33Kogure, G.S., et al., Resistance Exercise Impacts Lean Muscle Mass in Women with Polycystic Ovary Syndrome. Med Sci Sports Exerc, 2016. 48(4): p. 589-98.

34Benson, S., et al., Disturbed stress responses in women with polycystic ovary syndrome. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 2009. 34(5): p. 727-35.

35Black, P.H., The inflammatory response is an integral part of the stress response: Implications for atherosclerosis, insulin resistance, type II diabetes and metabolic syndrome X. Brain Behav Immun, 2003. 17(5): p. 350-64.

36Pasquali, R., et al., The hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis activity in obesity and the metabolic syndrome. Ann N Y Acad Sci, 2006. 1083: p. 111-28.

37Lynch, C.D., et al., Preconception stress increases the risk of infertility: results from a couple-based prospective cohort study–the LIFE study. Hum Reprod, 2014. 29(5): p. 1067-75.

38Wegner, M., et al., Effects of exercise on anxiety and depression disorders: review of meta- analyses and neurobiological mechanisms. CNS Neurol Disord Drug Targets, 2014. 13(6): p. 1002-14.

39Franasiak, J.M., et al., The nature of aneuploidy with increasing age of the female partner: a review of 15,169 consecutive trophectoderm biopsies evaluated with comprehensive chromosomal screening. Fertil Steril, 2014. 101(3): p. 656-663.e1.

40Menken, J., J. Trussell, and U. Larsen, Age and infertility. Science, 1986. 233(4771): p. 1389-94.

41Sharpe, A., et al., Metformin for ovulation induction (excluding gonadotrophins) in women with polycystic ovary syndrome. Cochrane Database Syst Rev, 2019. 12(12): p. Cd013505.

42Legro, R.S., et al., Diagnosis and treatment of polycystic ovary syndrome: an Endocrine Society clinical practice guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab, 2013. 98(12): p. 4565-92.

43Legro, R.S., et al., Randomized Controlled Trial of Preconception Interventions in Infertile Women With Polycystic Ovary Syndrome. J Clin Endocrinol Metab, 2015. 100(11): p. 4048-58.

44Legro, R.S., et al., Benefit of Delayed Fertility Therapy With Preconception Weight Loss Over Immediate Therapy in Obese Women With PCOS. J Clin Endocrinol Metab, 2016. 101(7): p. 2658-66.

45Balen, A.H., et al., The management of anovulatory infertility in women with polycystic ovary syndrome: an analysis of the evidence to support the development of global WHO guidance. Hum Reprod Update, 2016. 22(6): p. 687-708.

46Legro, R.S., et al., Letrozole versus clomiphene for infertility in the polycystic ovary syndrome. N Engl J Med, 2014. 371(2): p. 119-29.

47Klement, A.H. and R.F. Casper, The use of aromatase inhibitors for ovulation induction. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol, 2015. 27(3): p. 206-9.

48Amer, S.A., et al., Double-blind randomized controlled trial of letrozole versus clomiphene citrate in subfertile women with polycystic ovarian syndrome. Hum Reprod, 2017. 32(8): p. 1631-1638.

49Mejia, R.B., et al., A randomized controlled trial of combination letrozole and clomiphene citrate or letrozole alone for ovulation induction in women with polycystic ovary syndrome. Fertil Steril, 2019. 111(3): p. 571-578.e1.

50Al-Hussaini, T.K., et al., Premature ovarian failure/dysfunction following surgical treatment of polycystic ovarian syndrome: A case series. Middle East Fertility Society Journal, 2017. 22(3): p. 233-235.

51Moridi, I., et al., The Association between Vitamin D and Anti-Müllerian Hormone: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Nutrients, 2020. 12(6).

52Fang, F., et al., Effect of vitamin D supplementation on polycystic ovary syndrome: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Complement Ther Clin Pract, 2017. 26: p. 53-60.

53Shojaei-Zarghani, S. and M. Rafraf, Resveratrol and Markers of Polycystic Ovary Syndrome: a Systematic Review of Animal and Clinical Studies. Reprod Sci, 2021.

54Chu, J., et al., Vitamin D and assisted reproductive treatment outcome: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Hum Reprod, 2018. 33(1): p. 65-80.

55Zhang, H., et al., Meta-analysis of the effect of the maternal vitamin D level on the risk of spontaneous pregnancy loss. Int J Gynaecol Obstet, 2017. 138(3): p. 242-249.

56Pilz, S., et al., The Role of Vitamin D in Fertility and during Pregnancy and Lactation: A Review of Clinical Data. Int J Environ Res Public Health, 2018. 15(10).

57Mai, Z., et al., Comparison of Cumulative Live Birth Rate Between Aged PCOS Women and Controls in IVF/ICSI Cycles. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne), 2021. 12: p. 724333.

58Tannus, S., et al., Prevalence, clinical characteristics, and reproductive outcomes of polycystic ovary syndrome in older women referred for tertiary fertility care. Arch Gynecol Obstet, 2018. 297(4): p. 1037-1042.

59Mellembakken, J.R., et al., Sustained fertility from 22 to 41 years of age in women with polycystic ovarian syndrome. Hum Reprod, 2011. 26(9): p. 2499-504.

60Hwang, Y.I., et al., Fertility of patients with polycystic ovary syndrome undergoing in vitro fertilization by age. Int J Gynaecol Obstet, 2016. 135(1): p. 91-5.

As a Nutritionist, I’m continuing my mission to help women like you, beat PCOS. Evidence-based diet and lifestyle interventions helped me overcome five years of infertility. I fell pregnant naturally after multiple failed IVF cycles. Along the way, my other PCOS symptoms went away too. This experience taught me how to combine the latest science with a pragmatic approach to habit change. I’ve now helped thousands of other women achieve life-changing results, and I love for you to be the next PCOS success story. Learn more about me and what I do here.

Co-Authors

This blog post has been critically reviewed to ensure accurate interpretation and presentation of the scientific literature by Dr. Jessica A McCoy, Ph.D. Dr McCoy has a master’s degree in cellular and molecular biology, and a doctorate in reproductive biology and environmental health. She currently serves as a University professor at the College of Charleston, South Carolina.

This blog post has also been medically reviewed and approved by Dr. Sarah Lee, M.D. Dr. Lee is a board-certified Physician practicing with Intermountain Healthcare in Utah. She obtained a Bachelor of Science in Biology from the University of Texas at Austin before earning her Doctor of Medicine from UT Health San Antonio.

Are there any specific foods that are commonly thought to be healthy, but actually worsen PCOS symptoms? What should women with PCOS be cautious about consuming in their diets?”,

“refusal

Hi there! This blog gives a pretty thorough explanation of foods to avoid. After reading it you will probably start to recognize healths trends that can be more harmful to PCOS than helpful like juicing, gluten-free health foods that are high in sugar, low-fat foods etc.