I’ve seen fertility clinics claim that “women with PCOS show sustained fertility with advancing age”. Other experts say that “the best time for women with PCOS to get pregnant is before they turn 30”. Without essential further context, both of these statements are misleading.

In this article, I explain why. I also explore the most salient considerations when deciding the best time to start or grow your family.

As you’ll see, if you’re thinking about getting pregnant with PCOS, then switching to a PCOS diet is the most important thing to do. Making this change is what my free 30-Day PCOS Diet Challenge is all about. The results speak for themselves.

Effects of Age on Natural Fertility

Age is important for fertility, but not as important as you might think.

Natural fertility peaks in your late teens to early twenties. But that’s unlikely to be the best age to get pregnant with PCOS. This is seldom the right age from a lifestyle and relationship perspective.

Putting that aside though, it’s also not great in terms of your journey through PCOS. Many women will be new to their diagnosis at this age. They’ve likely been given ineffective treatments that only mask the symptoms. See my article on PCOS birth control to understand all the reasons to avoid this treatment. Your teens and early twenties are also a time when your PCOS starts to get out of control.

Weight gain and/or irregular periods are the biggest causes of PCOS infertility. But once you get these under control, your chances of getting pregnant look similar to non-PCOS women. That’s when age-related fertility decline is likely to be a more important consideration.

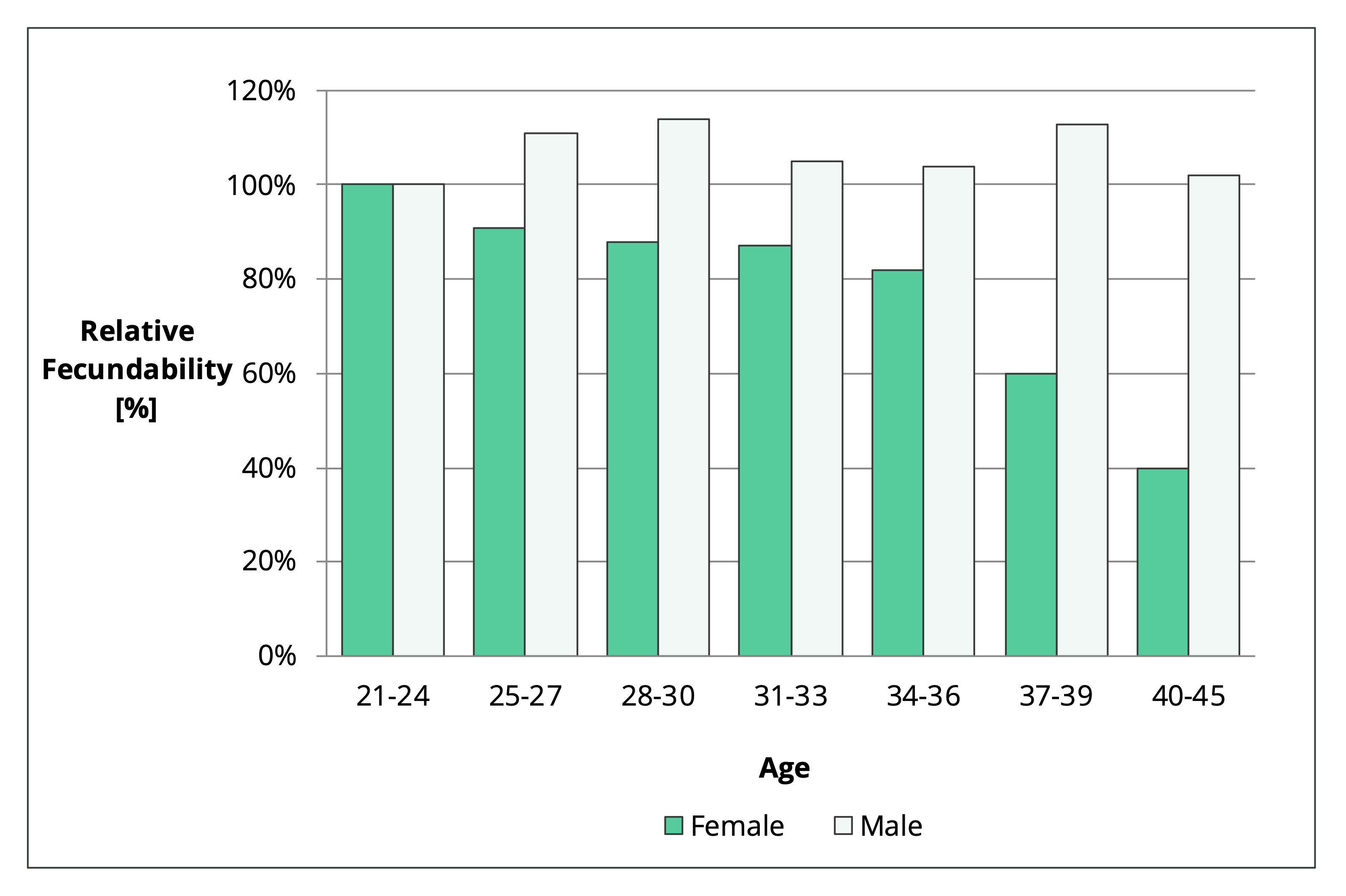

Here’s some data on a general, non-PCOS population, to put this into context.

Natural fertility declines slowly with age between 24 and 36 years old [1]. A 36-year-old retains more than 80% of their peak fertility. But fertility declines faster in your late thirties. On average, a 39-year-old woman is about 40% less fertile than she was in her early twenties.

Figure 1. Relative change in fecundability with age. The 21–24-year-old group is the reference level. Values below 100% represent a decline in fertility, while levels above 100% show enhanced fertility.

So, biology suggests that it’s easier to get pregnant in your early twenties. But that’s on average.

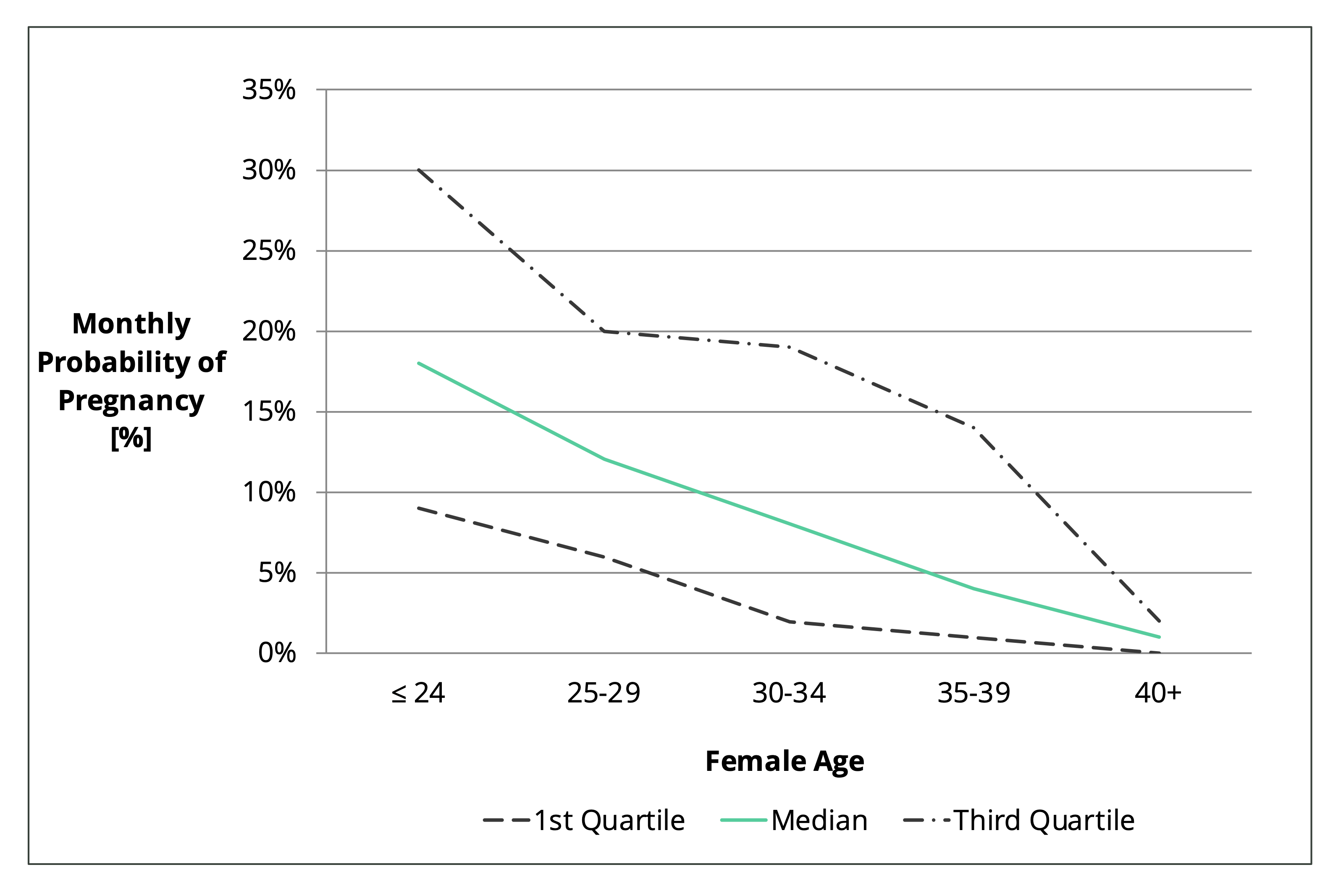

As I explain in my article on the chances of getting pregnant with PCOS, there’s a large variation in fertility at any given age.

Figure 2. Monthly probability of falling pregnant for Japanese couples trying to conceive naturally [2].

As can be seen in Figure 2, the most fertile 25% of 35-39 year old women have a 14% chance of falling pregnant each month (see third quartile line). This is higher than the 12% average for 25–29-year-olds (see median line). This is because with age, comes wisdom. And wisdom means making changes that improve fertility.

For women with PCOS, this means getting a regular cycle and achieving a healthy body weight. “Older” women are more likely to track fertility and predict ovulation. This helps a lot. They’re also less likely to smoke and drink alcohol which works in your favor when trying to conceive.

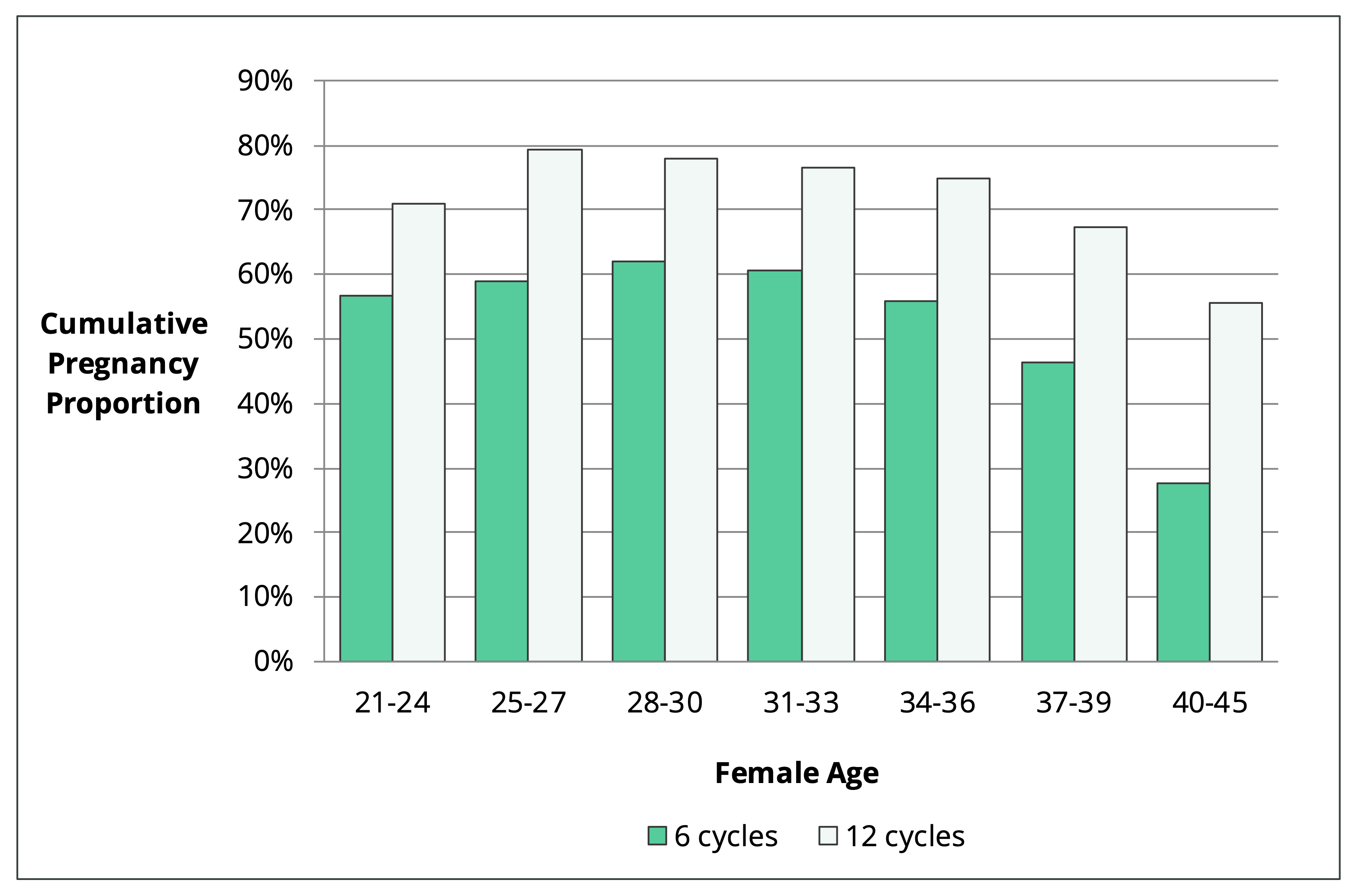

Figure 3, shows the percentage of women who fell pregnant over 6 and 12 cycles. This data was collected from 2962 couples who had been trying to conceive for three cycles or less. These women didn’t have any history of infertility.

Figure 3. Cumulative pregnancy proportion within 6 and 12 cycles by female age [1].

The most interesting finding from this study is that natural fertility is higher in your early thirties than it is in your early twenties. This increase in pregnancy rate shows how all the other aspects of your lifestyle can delay age-related fertility decline.

In a healthy population, more than half of women aged 40-45 years old will get pregnant within a year of trying. This is much greater than people are often led to believe.

With the right diet and support, women with PCOS can achieve this too.

Importance of Cycle Regularity vs Age

The regularity of your period is the most important factor when determining the best age to get pregnant with PCOS. If you don’t get a regular period, then your chances of having a baby without medical intervention are depressingly slim. In many ways, the dependability of your cycle is more important than how old you are.

Approximately two-thirds of women with PCOS don’t ovulate regularly [3]. About 70-80% of women with unmanaged PCOS experience infertility [4, 5]. If you want to get pregnant with PCOS, then you need to beat these odds.

Women with PCOS have irregular periods because of poor hormone regulation. This is why many doctors jump to pharmaceutical solutions that alter hormone levels. Think birth control, metformin, clomid, letrozole, gonadotropins, etc.

These treatments help with ovulation. But they don’t address egg quality issues, implantation, or the health of your pregnancy. As I explain in my article, Can You Get Pregnant with PCOS, these other factors reduce fertility in women with PCOS. PCOS impairs ovulation, egg quality, and implantation [6-14]. Women with PCOS are also more likely to miscarry [15-17].

Another problem with ovulation induction drugs is that they fail to address the reason your hormones are out of balance in the first place. In PCOS, hormonal dysregulation occurs as a result of poor insulin regulation and chronic inflammation. These are the primary drivers of all PCOS symptoms [18-24].

Solving these problems should be the goal of anyone with PCOS that’s trying to conceive. Regardless of age. This is true whether you’re trying naturally or you’re seeking medical help. Sometimes taking 6-12 months to get your PCOS under control first can reduce the time it takes to have a baby. Your natural fertility may be better today from an age perspective. But your birth outcomes may be more dependent on your metabolic health.

This brings us to the next most important consideration…

Importance of Metabolic Health vs Age

Your metabolic health has a massive impact on your chances of getting pregnant with PCOS. In many ways, health status is more important than age. Taking time to improve your cardiovascular health can shorten the overall time it takes to have a child. It also increases the chances that your future child will be healthy too.

As I said already, PCOS affects ovulation and egg quality [6-9]. But it’s well known that being overweight makes this problem worse [8, 10, 11]. PCOS also affects implantation [12, 13]. But again, this issue is worse if you’re overweight [14]. Studies on weight-loss programs have shown that dietary change can shift this paradigm [25].

Recent meta-analyses on IVF patients suggest the risk of miscarriage is about 40-60% higher for PCOS women [15, 16]. This is true for lean women too which is why health isn’t just about body weight [17]. Lean women with PCOS suffer also from insulin resistance and other metabolic abnormalities [26].

Once a successful pregnancy is established, PCOS women are more prone to pregnancy complications. A 2019 meta-analysis assessed these relative risks [15]. They found that women with PCOS have more than two and a half times the risk of developing gestational diabetes. Despite popular belief, this condition has no impact on other pregnancy complications. But it increases the risks of second-trimester miscarriage [27]. Women with PCOS have twice the risk of pregnancy-induced high blood pressure and large-for-age babies. Preterm birth rate risks are also increased by 60%.

Many of these risks are lower in PCOS women of normal weight and in those without insulin resistance [28]. Women that manage their metabolic health are more likely to have healthy pregnancies. Studies show that weight loss, in particular, mitigates pregnancy risks [29, 30].

How To Improve Your Cycle & Metabolic Health

As mentioned above, insulin regulation and inflammation are central to PCOS infertility. Studies show that these factors are largely driven by poor gut health [13, 31]. Through their effects on the gut, your diet and lifestyle have a huge impact on your PCOS symptoms [32].

Diet provides the most meaningful way to improve your cycle and metabolic health. For example, there are seven foods to avoid with PCOS. Managing your mix of ingredients to optimize your macros for PCOS is also very valuable. This is what my free 30-Day PCOS Diet Challenge is all about. For a sample of recipes that embrace these ideas, download my free 3-Day Meal Plan here.

I describe other important evidence-based natural treatments in my article How to Get Pregnant with PCOS. These include supplements, exercise, and stress management. Each of these interventions may be small on its own, but when combined with diet, they can make a big difference.

Diet and lifestyle interventions are effective PCOS treatments. This makes it worthwhile to consider delaying conception before trying to conceive. I don’t say this flippantly. I was 31 when I first started trying to conceive, but I didn’t have my baby until I was 36. I understand the pressure. Some of this is biological. But personal and cultural expectations often make this worse. The reality is that for most women with PCOS, your cycle and metabolic health matter more than how old you are. Even though you want that baby right now, sometimes taking time to work on your health first is the better course of action. A brief detour can often be faster than plowing ahead into a traffic jam.

When Age Matters

You now have a bucket-load of data describing the effects of age on natural fertility. It’s probably not as bad as you thought. You understand the importance of your cycle and metabolic health to fertility too. You also now know that there are many steps you can take on your own to maximize your chances of getting pregnant.

The take home is that for younger women, it can make sense to wait a while. Focus on the proven interventions that can restore your period and reverse insulin resistance. This will help you get pregnant. But it’ll also be better for both you and your children in the long run.

For women in their late thirties and forties, the calculus looks a little different. If you’re new to a PCOS-friendly diet and lifestyle, expediting the fertility process makes more sense. In my experience, it usually takes at least 6-12 months to transform your health. You can get great results within weeks, but you’ll likely need longer to get things optimized. It can make good sense to seek fertility treatment while you go about making these changes.

IVF Sustains Fertility More for PCOS Women

If you’re considering medical fertility treatments, then there’s an upside to having PCOS.

This is where that misleading statement I mentioned at the top of the article comes from. The chances of having a baby through IVF change less with age for women with PCOS. So, it’s true that “women with PCOS show sustained fertility with advancing age”. But only if they’re doing IVF.

Women with PCOS have higher ovarian reserve than non-PCOS women of a similar age. This means that when you undergo egg harvesting, you’re likely to get more eggs. More eggs equals more embryos per cycle. This means you can do more embryo transfer cycles, which increases your chances of having a baby overall [33, 34].

One IVF study on women with PCOS found that birth rates were stable between 22 and 41 years of age [35]. This was supported by a similar study. PCOS women over 40 had comparable success rates to those aged 35 to 40 [36]. Another study found that peak fertility was maintained in PCOS women until 38 years of age [37].

This is great news for “older” women that are wanting to have a child. If you have PCOS and you’re going down the IVF path, you’re much less affected by age-related fertility decline. That can buy you more time to get your period and metabolic health sorted.

The Bottom Line

The best age to get pregnant with PCOS doesn’t just depend on how old you are. Your menstrual cycle and metabolic health may be more important. Getting a regular period is essential for conceiving naturally. Reversing insulin resistance and losing weight increases your odds of a healthy pregnancy. In many cases, you may be better off getting your PCOS under control before trying to conceive. Even if this takes 6-12 months, the improvements in your natural fertility are likely to be much greater than the losses due to age.

If you’re going down the path of IVF, then you have more time on your hands. PCOS women maintain good IVF success rates well into their forties.

Regardless of your method of conception, switching to a PCOS diet makes it more likely you’ll have a healthy, happy pregnancy. Get started today by joining my free 30-Day PCOS Diet Challengea. You can also download my free 3-Day Meal Plan here.

Author

As a Nutritionist, I’m continuing my mission to help women like you, beat PCOS. Evidence-based diet and lifestyle interventions helped me overcome five years of infertility. I fell pregnant naturally after multiple failed IVF cycles. Along the way, my other PCOS symptoms went away too. This experience taught me how to combine the latest science with a pragmatic approach to habit change. I’ve now helped thousands of other women achieve life-changing results, and I love for you to be the next PCOS success story. Learn more about me and what I do here.

References

1Wesselink, A.K., et al., Age and fecundability in a North American preconception cohort study. Am J Obstet Gynecol, 2017. 217(6): p. 667.e1-667.e8.

2Konishi, S., et al., Fecundability and Sterility by Age: Estimates Using Time to Pregnancy Data of Japanese Couples Trying to Conceive Their First Child with and without Fertility Treatment. Int J Environ Res Public Health, 2021. 18(10).

3Hart, R., PCOS and infertility. Panminerva Med, 2008. 50(4): p. 305-14.

4Melo, A.S., R.A. Ferriani, and P.A. Navarro, Treatment of infertility in women with polycystic ovary syndrome: approach to clinical practice. Clinics (Sao Paulo), 2015. 70(11): p. 765-9.

5Joham, A.E., et al., Prevalence of infertility and use of fertility treatment in women with polycystic ovary syndrome: data from a large community-based cohort study. J Womens Health (Larchmt), 2015. 24(4): p. 299-307.

6Patil, K., et al., Compromised Cumulus-Oocyte Complex Matrix Organization and Expansion in Women with PCOS. Reprod Sci, 2021.

7Chang, R.J. and H. Cook-Andersen, Disordered follicle development. Mol Cell Endocrinol, 2013. 373(1-2): p. 51-60.

8Palomba, S., J. Daolio, and G.B. La Sala, Oocyte Competence in Women with Polycystic Ovary Syndrome. Trends Endocrinol Metab, 2017. 28(3): p. 186-198.

9Patel, S.S. and B.R. Carr, Oocyte quality in adult polycystic ovary syndrome. Semin Reprod Med, 2008. 26(2): p. 196-203.

10Gonzalez, M.B., et al., Inflammatory markers in human follicular fluid correlate with lipid levels and Body Mass Index. J Reprod Immunol, 2018. 130: p. 25-29.

11Broughton, D.E. and K.H. Moley, Obesity and female infertility: potential mediators of obesity’s impact. Fertil Steril, 2017. 107(4): p. 840-847.

12Giudice, L.C., Endometrium in PCOS: Implantation and predisposition to endocrine CA. Best Pract Res Clin Endocrinol Metab, 2006. 20(2): p. 235-44.

13He, F.F. and Y.M. Li, Role of gut microbiota in the development of insulin resistance and the mechanism underlying polycystic ovary syndrome: a review. J Ovarian Res, 2020. 13(1): p. 73.

14Schulte, M.M., J.H. Tsai, and K.H. Moley, Obesity and PCOS: the effect of metabolic derangements on endometrial receptivity at the time of implantation. Reprod Sci, 2015. 22(1): p. 6-14.

15Sha, T., et al., A meta-analysis of pregnancy-related outcomes and complications in women with polycystic ovary syndrome undergoing IVF. Reprod Biomed Online, 2019. 39(2): p. 281-293.

16Matorras, R., et al., Polycystic ovarian syndrome and miscarriage in IVF: systematic revision of the literature and meta-analysis. Arch Gynecol Obstet, 2022.

17Luo, L., et al., Early miscarriage rate in lean polycystic ovary syndrome women after euploid embryo transfer – a matched-pair study. Reprod Biomed Online, 2017. 35(5): p. 576-582.

18Barrea, L., et al., Source and amount of carbohydrate in the diet and inflammation in women with polycystic ovary syndrome. Nutr Res Rev, 2018. 31(2): p. 291-301.

19Carvalho, L.M.L., et al., Polycystic Ovary Syndrome as a systemic disease with multiple molecular pathways: a narrative review. Endocr Regul, 2018. 52(4): p. 208-221.

20González, F., Inflammation in Polycystic Ovary Syndrome: underpinning of insulin resistance and ovarian dysfunction. Steroids, 2012. 77(4): p. 300-5.

21González, F., et al., Hyperandrogenism sensitizes mononuclear cells to promote glucose-induced inflammation in lean reproductive-age women. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab, 2012. 302(3): p. E297-306.

22Popovic, M., G. Sartorius, and M. Christ-Crain, Chronic low-grade inflammation in polycystic ovary syndrome: is there a (patho)-physiological role for interleukin-1? Seminars in Immunopathology, 2019. 41(4): p. 447-459.

23Rudnicka, E., et al., Chronic Low Grade Inflammation in Pathogenesis of PCOS. Int J Mol Sci, 2021. 22(7).

24Wang, J., et al., Hyperandrogenemia and insulin resistance: The chief culprit of polycystic ovary syndrome. Life Sciences, 2019. 236.

25Abdulkhalikova, D., et al., The Lifestyle Modifications and Endometrial Proteome Changes of Women With Polycystic Ovary Syndrome and Obesity. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne), 2022. 13: p. 888460.

26Toosy, S., R. Sodi, and J.M. Pappachan, Lean polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS): an evidence-based practical approach. Journal of Diabetes and Metabolic Disorders, 2018. 17(2): p. 277-285.

27Fougner, S.L., et al., No impact of gestational diabetes mellitus on pregnancy complications in women with PCOS, regardless of GDM criteria used. PLoS One, 2021. 16(7): p. e0254895.

28Wang, T., et al., [Pregnancy complications among women with polycystic ovary syndrome in China: a Meta-analysis]. Zhong Nan Da Xue Xue Bao Yi Xue Ban, 2017. 42(11): p. 1300-1310.

29Yang, S.T., et al., Association between Pre-Pregnancy Overweightness/Obesity and Pregnancy Outcomes in Women with Polycystic Ovary Syndrome: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Int J Environ Res Public Health, 2022. 19(15).

30Effect of diet and physical activity based interventions in pregnancy on gestational weight gain and pregnancy outcomes: meta-analysis of individual participant data from randomised trials. Bmj, 2017. 358: p. j3119.

31Tremellen, K. and K. Pearce, Dysbiosis of Gut Microbiota (DOGMA)–a novel theory for the development of Polycystic Ovarian Syndrome. Med Hypotheses, 2012. 79(1): p. 104-12.

32Sivasankari, R. and B. Usha, Reshaping the Gut Microbiota Through Lifestyle Interventions in Women with PCOS: A Review. Indian J Microbiol, 2022. 62(3): p. 351-363.

33Mai, Z., et al., Comparison of Cumulative Live Birth Rate Between Aged PCOS Women and Controls in IVF/ICSI Cycles. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne), 2021. 12: p. 724333.

34Tannus, S., et al., Prevalence, clinical characteristics, and reproductive outcomes of polycystic ovary syndrome in older women referred for tertiary fertility care. Arch Gynecol Obstet, 2018. 297(4): p. 1037-1042.

35Mellembakken, J.R., et al., Sustained fertility from 22 to 41 years of age in women with polycystic ovarian syndrome. Hum Reprod, 2011. 26(9): p. 2499-504.

36Li, J., et al., A Slower Age-Related Decline in Treatment Outcomes After the First Ovarian Stimulation for in vitro Fertilization in Women With Polycystic Ovary Syndrome. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne), 2019. 10: p. 834.

37Hwang, Y.I., et al., Fertility of patients with polycystic ovary syndrome undergoing in vitro fertilization by age. Int J Gynaecol Obstet, 2016. 135(1): p. 91-5.

As a Nutritionist, I’m continuing my mission to help women like you, beat PCOS. Evidence-based diet and lifestyle interventions helped me overcome five years of infertility. I fell pregnant naturally after multiple failed IVF cycles. Along the way, my other PCOS symptoms went away too. This experience taught me how to combine the latest science with a pragmatic approach to habit change. I’ve now helped thousands of other women achieve life-changing results, and I love for you to be the next PCOS success story. Learn more about me and what I do here.

“Since my diagnosis and journey to conceive began, I have found out so many other women I know have it and have also had problems conceiving. I think a lot of us had the symptoms when we were teenagers, but went on the pill, which masked the condition for years.”

PCOS sufferer