My prior battle with acne was typical for a woman with PCOS. It started when I was young and plagued me for 15 years. By the time I was 12, it was so bad my mom took me to a dermatologist. She put me on Retin-A and antibiotics. I also went on birth control and used peroxide-based cleansers in a flailing effort to keep my acne in check.

I avoided tank tops and shoulder-less dresses because I was so self-conscious about my PCOS back acne. Like many young women in my situation, I also spent a small fortune on concealers.

The miraculous change I eventually experienced had nothing to do with the things I’d tried before. To my surprise, it was a spin-off effect of changing my diet.

Only a few months before, I’d started following a PCOS diet. This is what I share during my free 30-Day PCOS Diet Challenge. While it wasn’t easy at the time, it’s now been over 10 years since I’ve had an acne breakout. There’s zero chance I’ll ever go back to my old way of eating.

I’ve now run hundreds of thousands of women through my 30-Day Challenge. Beyond my own experiences, these women have shown me that acne is curable. It’s often the first PCOS symptom to improve when following a PCOS diet.

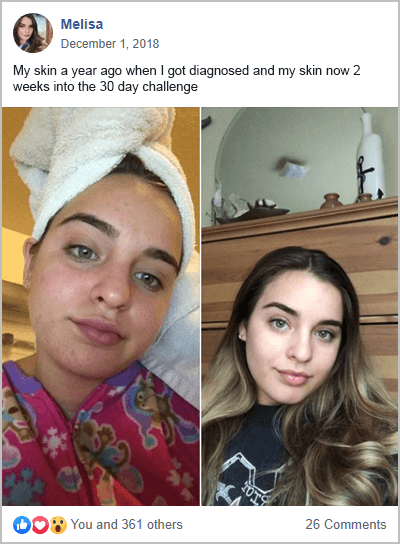

Melisa is a great example of this.

Here are three things about PCOS acne, I wished I’d known about sooner.

1. Conventional Treatments are Band-Aid Solutions

It took me a long time to figure this out. But now that I understand the root cause of PCOS acne, I can see why everything I tried in the past failed.

Most conventional PCOS acne treatments use one of two methods. They try to physically remove it or they alter hormone levels. These solutions fail to address the underlying problem. They might mask the symptoms for a time. But the acne will be back as soon as you stop treatment.

The other big downside is the adverse effects of many medications. These are under-explained to almost every woman I’ve ever met with PCOS. I’ve learned about the long-term harms of many medications the hard way.

As a naïve teenager, I went on antibiotics just to treat my acne. I sorely regret this decision now that I know how detrimental it has been to my health. Everyone these days knows about the risk of antibiotic-resistant microbes. What’s less well-known is that long-term antibiotic use destroys your gut flora [1, 2].

Dysbiosis of the gut microbiome can account for all three components of PCOS [3, 4].

- Anovulation/menstrual irregularity

- Hyper-androgenism (i.e. acne, hirsutism)

- The development of multiple small ovarian cysts.

The gut microbiome is a core component of your immune system. Long-term antibiotic use is completely counterproductive to your health and well-being.

Going on birth control is another mistake I wished I hadn’t made.

Oral contraceptives are the most common PCOS acne treatment. But that doesn’t mean it’s a good idea. In my opinion, oral contraceptives should be a last resort rather than a first-line therapy. In my article on PCOS birth control, I describe the hazards of this treatment.

Hormonal birth control has been shown to:

- Deplete nutrients [5-7].

- Reduce insulin sensitivity [8-10].

- Drive inflammation [11, 12].

- Increase cancer risks [13, 14].

- Increase the risk of blood clotting disorders [15].

- Be associated with adverse effects on mental health [16-20].

Some doctors also prescribe metformin for the treatment of PCOS cystic acne. There’s no doubt that metformin helps with PCOS acne [21, 22]. But again, this doesn’t make it a good option. This is especially true when there are better solutions with no negative side effects (see below).

Metformin is no longer recommended as a first-line PCOS therapy for “any indication” [23]. I explain the many problems with metformin for PCOS here. Metformin has limited or no benefit for weight loss or fertility [24-26]. Metformin is known to deplete nutrients [27-30]. Side effects are also very common [31]. These include diarrhea, heartburn, nausea, abdominal pain, bloating, and retching [32].

2. Inflammation is Key to Curing PCOS Acne

If you want to cure PCOS acne for good, then you need to understand the root causes.

Until fairly recently, doctors believed that acne was caused by elevated androgens, like testosterone. This idea is outdated and incorrect. It’s now known that acne is primarily an inflammatory disease [33-36].

Inflammation is also one of the underlying mechanisms that cause PCOS [37-41].

PCOS women all have a problem with chronic low-grade inflammation. PCOS women with acne see this inflammation manifest on their skin. This is what happened to me.

If you want to cure PCOS acne, then you need to overcome inflammation. Take it from someone that stumbled onto this finding. It was only after changing my diet that my PCOS acne disappeared forever.

3. Diet is the Best Acne Treatment

A PCOS diet eliminates inflammatory foods. See my foods to avoid with PCOS here.

A PCOS diet also promotes the consumption of anti-inflammatory foods. Foods like non-starchy vegetables, and many nuts and seeds. Oily fish and olive oil are also really good in this department.

Most importantly, a PCOS diet reduces inflammation by promoting better insulin regulation. Insulin resistance causes inflammation and is directly involved in the formation of acne [42, 43].

Dietary change is the best way to reverse insulin resistance. You can optimize your PCOS macros and switch to slower-digesting carbohydrate foods. Eating more fiber also improves insulin sensitivity [44, 45]. Studies have shown that reductions in acne can be achieved just by lowering the glycemic load of your diet [46, 47].

It was through these changes that I was able to cure my PCOS acne for good.

So have many other women that have taken part in my free 30-Day PCOS Diet Challenge.

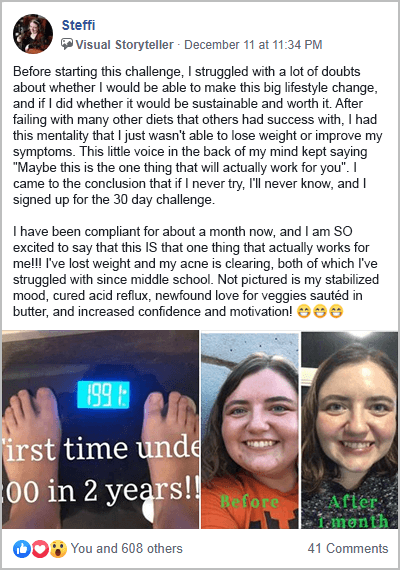

Steffi, for example, spent years struggling with other diets. She was skeptical that she’d be able to make a PCOS diet sustainable. Fortunately, she gave it a go. Within a month her acne began to clear. Not only that, but she also lost weight, her mood stabilized, and her acid reflux resolved. A year on, she has continued to maintain this new way of life. She’s also discovered a newfound appreciation for her body.

Katy is another great example. Six months after changing her diet, her skin cleared up without medication. She lost weight and resolved her previous gut issues. After taking part in my Beat PCOS 10-Week Program Katy now has her entire family eating healthier.

For a sample of PCOS-friendly recipes, download this free 3-Day PCOS Meal Plan.

Say Goodbye to PCOS Acne for Good

I’m thankful I was finally able to get rid of my acne. But I wish I’d been able to take the right steps sooner. I wish I hadn’t wasted so much time on solutions that didn’t work.

I know diet changes aren’t easy to get used to. They take time, money, and a lot of dedication. As a former sugarholic, I remember how painful it was to part ways with my addiction. But acne is a sign of a much wider problem.

It’s the cliché tip of the PCOS iceberg.

We can flip this ominous imagery around though. Changing how you eat addresses the root causes of PCOS. This doesn’t just cure your acne. A PCOS diet also leads to better health and fertility.

If you’re ready to take action, then sign-up for my free 30-Day PCOS-Diet Challenge. In a few months, when you wake up to clear skin, you’ll be so glad you did.

Author

As a Nutritionist, I’m continuing my mission to help women like you, beat PCOS. Evidence-based diet and lifestyle interventions helped me overcome five years of infertility. I fell pregnant naturally after multiple failed IVF cycles. Along the way, my other PCOS symptoms went away too. This experience taught me how to combine the latest science with a pragmatic approach to habit change. I’ve now helped thousands of other women achieve life-changing results, and I love for you to be the next PCOS success story. Learn more about me and what I do here.

References

1Jernberg, C., et al., Long-term impacts of antibiotic exposure on the human intestinal microbiota. Microbiology (Reading), 2010. 156(Pt 11): p. 3216-3223.

2Lange, K., et al., Effects of Antibiotics on Gut Microbiota. Dig Dis, 2016. 34(3): p. 260-8.

3Tremellen, K. and K. Pearce, Dysbiosis of Gut Microbiota (DOGMA)–a novel theory for the development of Polycystic Ovarian Syndrome. Med Hypotheses, 2012. 79(1): p. 104-12.

4He, F.F. and Y.M. Li, Role of gut microbiota in the development of insulin resistance and the mechanism underlying polycystic ovary syndrome: a review. J Ovarian Res, 2020. 13(1): p. 73.

5Thorp, V.J., Effect of oral contraceptive agents on vitamin and mineral requirements. J Am Diet Assoc, 1980. 76(6): p. 581-4.

6Webb, J.L., Nutritional effects of oral contraceptive use: a review. J Reprod Med, 1980. 25(4): p. 150-6.

7Palmery, M., et al., Oral contraceptives and changes in nutritional requirements. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci, 2013. 17(13): p. 1804-13.

8Mastorakos, G., et al., Effects of two forms of combined oral contraceptives on carbohydrate metabolism in adolescents with polycystic ovary syndrome. Fertil Steril, 2006. 85(2): p. 420-7.

9Piltonen, T., et al., Oral, transdermal and vaginal combined contraceptives induce an increase in markers of chronic inflammation and impair insulin sensitivity in young healthy normal-weight women: a randomized study. Hum Reprod, 2012. 27(10): p. 3046-56.

10Petersen, K.R., Pharmacodynamic effects of oral contraceptive steroids on biochemical markers for arterial thrombosis. Studies in non-diabetic women and in women with insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. Dan Med Bull, 2002. 49(1): p. 43-60.

11Hoeger, K., et al., The impact of metformin, oral contraceptives, and lifestyle modification on polycystic ovary syndrome in obese adolescent women in two randomized, placebo-controlled clinical trials. J Clin Endocrinol Metab, 2008. 93(11): p. 4299-306.

12Williams, W.V., Hormonal contraception and the development of autoimmunity: A review of the literature. Linacre Q, 2017. 84(3): p. 275-295.

13Mørch, L.S., et al., Contemporary Hormonal Contraception and the Risk of Breast Cancer. N Engl J Med, 2017. 377(23): p. 2228-2239.

14Conz, L., et al., Levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system and breast cancer risk: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand, 2020. 99(8): p. 970-982.

15Lidegaard, O., et al., Venous thrombosis in users of non-oral hormonal contraception: follow-up study, Denmark 2001-10. Bmj, 2012. 344: p. e2990.

16Skovlund, C.W., et al., Association of Hormonal Contraception With Depression. JAMA Psychiatry, 2016. 73(11): p. 1154-1162.

17Pérez-López, F.R., et al., Hormonal contraceptives and the risk of suicide: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol, 2020. 251: p. 28-35.

18Edwards, A.C., et al., Oral contraceptive use and risk of suicidal behavior among young women. Psychol Med, 2020: p. 1-8.

19Skovlund, C.W., et al., Association of Hormonal Contraception With Suicide Attempts and Suicides. Am J Psychiatry, 2018. 175(4): p. 336-342.

20Sharma, R., et al., Oral contraceptive use, especially during puberty, alters resting state functional connectivity. Horm Behav, 2020. 126: p. 104849.

21Sharma, S., et al., Efficacy of Metformin in the Treatment of Acne in Women with Polycystic Ovarian Syndrome: A Newer Approach to Acne Therapy. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol, 2019. 12(5): p. 34-38.

22Yen, H., et al., Metformin Therapy for Acne in Patients with Polycystic Ovary Syndrome: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Am J Clin Dermatol, 2021. 22(1): p. 11-23.

23Barbieri, R.L.E., D.A., Metformin for treatment of the polycystic ovary syndrome. UpToDate, 2018.

24Legro, R.S., et al., Diagnosis and treatment of polycystic ovary syndrome: an Endocrine Society clinical practice guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab, 2013. 98(12): p. 4565-92.

25Morley, L.C., et al., Insulin-sensitising drugs (metformin, rosiglitazone, pioglitazone, D-chiro-inositol) for women with polycystic ovary syndrome, oligo amenorrhoea and subfertility. Cochrane Database Syst Rev, 2017. 11(11): p. Cd003053.

26Tang, T., et al., Insulin-sensitising drugs (metformin, rosiglitazone, pioglitazone, D-chiro-inositol) for women with polycystic ovary syndrome, oligo amenorrhoea and subfertility. Cochrane Database Syst Rev, 2012(5): p. Cd003053.

27Laird, E.J., et al., Voluntary fortification is ineffective to maintain the vitamin B12 and folate status of older Irish adults: evidence from the Irish Longitudinal Study on Ageing (TILDA). Br J Nutr, 2018. 120(1): p. 111-120.

28Aroda, V.R., et al., Long-term Metformin Use and Vitamin B12 Deficiency in the Diabetes Prevention Program Outcomes Study. J Clin Endocrinol Metab, 2016. 101(4): p. 1754-61.

29Ting, R.Z., et al., Risk factors of vitamin B(12) deficiency in patients receiving metformin. Arch Intern Med, 2006. 166(18): p. 1975-9.

30Wakeman, M. and D.T. Archer, Metformin and Micronutrient Status in Type 2 Diabetes: Does Polypharmacy Involving Acid-Suppressing Medications Affect Vitamin B12 Levels? Diabetes Metab Syndr Obes, 2020. 13: p. 2093-2108.

31Florez, H., et al., Impact of metformin-induced gastrointestinal symptoms on quality of life and adherence in patients with type 2 diabetes. Postgrad Med, 2010. 122(2): p. 112-20.

32Bouchoucha, M., B. Uzzan, and R. Cohen, Metformin and digestive disorders. Diabetes Metab, 2011. 37(2): p. 90-6.

33Kircik, L.H., Advances in the Understanding of the Pathogenesis of Inflammatory Acne. J Drugs Dermatol, 2016. 15(1 Suppl 1): p. s7-10.

34Tanghetti, E.A., The role of inflammation in the pathology of acne. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol, 2013. 6(9): p. 27-35.

35Williams, H.C., R.P. Dellavalle, and S. Garner, Acne vulgaris. Lancet, 2012. 379(9813): p. 361-72.

36Zouboulis, C.C., E. Jourdan, and M. Picardo, Acne is an inflammatory disease and alterations of sebum composition initiate acne lesions. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol, 2014. 28(5): p. 527-32.

37Carvalho, L.M.L., et al., Polycystic Ovary Syndrome as a systemic disease with multiple molecular pathways: a narrative review. Endocr Regul, 2018. 52(4): p. 208-221.

38González, F., Inflammation in Polycystic Ovary Syndrome: underpinning of insulin resistance and ovarian dysfunction. Steroids, 2012. 77(4): p. 300-5.

39Popovic, M., G. Sartorius, and M. Christ-Crain, Chronic low-grade inflammation in polycystic ovary syndrome: is there a (patho)-physiological role for interleukin-1? Seminars in Immunopathology, 2019. 41(4): p. 447-459.

40Rostamtabar, M., et al., Pathophysiological roles of chronic low-grade inflammation mediators in polycystic ovary syndrome. J Cell Physiol, 2021. 236(2): p. 824-838.

41Rudnicka, E., et al., Chronic Low Grade Inflammation in Pathogenesis of PCOS. Int J Mol Sci, 2021. 22(7).

42Kumari, R. and D.M. Thappa, Role of insulin resistance and diet in acne. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol, 2013. 79(3): p. 291-9.

43Shimobayashi, M., et al., Insulin resistance causes inflammation in adipose tissue. J Clin Invest, 2018. 128(4): p. 1538-1550.

44Cutler, D.A., S.M. Pride, and A.P. Cheung, Low intakes of dietary fiber and magnesium are associated with insulin resistance and hyperandrogenism in polycystic ovary syndrome: A cohort study. Food Sci Nutr, 2019. 7(4): p. 1426-1437.

45Weickert, M.O. and A.F.H. Pfeiffer, Impact of Dietary Fiber Consumption on Insulin Resistance and the Prevention of Type 2 Diabetes. J Nutr, 2018. 148(1): p. 7-12.

46Kwon, H.H., et al., Clinical and histological effect of a low glycaemic load diet in treatment of acne vulgaris in Korean patients: a randomized, controlled trial. Acta Derm Venereol, 2012. 92(3): p. 241-6.

47Smith, R.N., et al., A low-glycemic-load diet improves symptoms in acne vulgaris patients: a randomized controlled trial. Am J Clin Nutr, 2007. 86(1): p. 107-15.

As a Nutritionist, I’m continuing my mission to help women like you, beat PCOS. Evidence-based diet and lifestyle interventions helped me overcome five years of infertility. I fell pregnant naturally after multiple failed IVF cycles. Along the way, my other PCOS symptoms went away too. This experience taught me how to combine the latest science with a pragmatic approach to habit change. I’ve now helped thousands of other women achieve life-changing results, and I love for you to be the next PCOS success story. Learn more about me and what I do here.