PCOS can’t be cured. But you can get to a point where you no longer meet the diagnostic criteria. This article explains how best to get there.

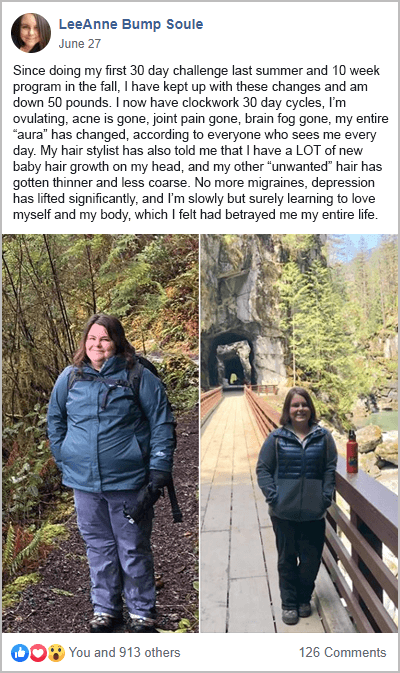

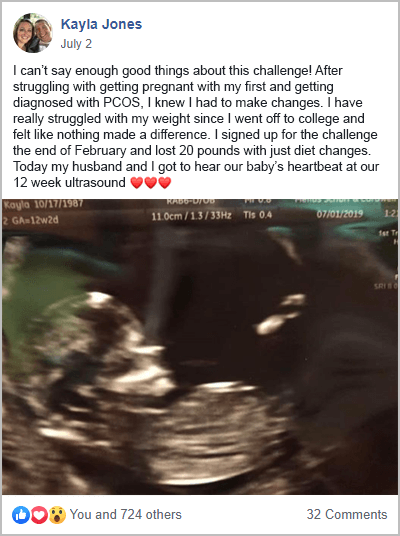

As evidenced by the success stories from my free 30-Day PCOS Diet Challenge, diet and lifestyle changes are key.

The Causes of PCOS

Many people will tell you that the cause of PCOS is unknown. This answer is both dismissive and unhelpful. Sure, there’s no cure for PCOS. But that’s because it isn’t a disease. It’s a syndrome. A syndrome is a collection of symptoms that show a disease is present. The diagnostic criteria are there to describe the symptoms. But to understand the causes, you need to go a little deeper.

Studies suggest that over 70% of PCOS has a genetic basis [1]. The health status of your mother during pregnancy also plays a big role. For example, elevated AMH and androgen levels during pregnancy “program” PCOS into offspring [2-5]. Prenatal exposure to endocrine-disrupting chemicals (EDCs) may also trigger fetal programming of PCOS [6, 7].

Genes and prenatal exposures set the stage for PCOS. But it’s also our environment and lifestyle factors during childhood that cause the syndrome to manifest [8, 9].

As an adult with PCOS, there are three key drivers of all your symptoms [10-15]. Elevated androgens, chronic inflammation, and poor insulin regulation.

Studies show that these factors are largely a result of imbalances in the gut microbiome [16, 17]. An unhealthy diet is also understood to be a key cause of PCOS [18]. By understanding these underlying mechanisms, you can start getting your symptoms under control.

1. Change Your Diet

The role of the gut microbiome and diet in PCOS pathology makes dietary change the most important intervention. It’s been shown that reshaping the gut microbiota through diet and lifestyle changes improves PCOS symptoms [19]. A PCOS diet reduces inflammation and improves insulin regulation. This lowers androgen levels keeping symptoms in check.

There are several key aspects of a PCOS-friendly diet. These steps all result in less inflammation and better insulin regulation.

A good PCOS diet is whole-food-based. Consuming mostly plant foods improves gut health and provides essential micronutrients. The best macros for PCOS are low-carb, high-fat, and moderate protein. This means including plenty of healthy whole-food sources of meat, seafood, and eggs. As well as all these positive changes, reducing or eliminating the 7 foods to avoid with PCOS can have the most profound impact on symptoms.

Collectively, these changes get results. Many participants from my free 30-Day PCOS Diet Challenge see improvements in their symptoms within weeks.

2. Consider Nutritional Supplements

Many supplements support a PCOS-friendly lifestyle.

For example, it’s known that women with PCOS are at risk of several nutrient deficiencies. These include calcium, potassium, and magnesium. Folate, vitamin C, and vitamin B12 deficiencies are also very common [20]. As I explain in my articles PCOS Birth Control and Metformin for PCOS, both of these therapeutics deplete nutrients [21-31]. Experts advise testing and supplementation with these treatments.

Several other supplements address the underlying mechanisms that cause PCOS. Fish oil and curcumin, for example, are well-known to reduce inflammation [32, 33]. Berberine also shows great potential for improving insulin resistance, blood lipids, and ovulation [34-37]. One meta-analysis found that berberine was as effective as metformin in improving insulin sensitivity [38].

One of the shortcomings of supplements is that they only work as long as you’re taking them. This means your supplements need to be safe, effective, and affordable to make them part of your PCOS management strategy. The two supplements that best fit this bill are vitamin D and inositol. You can read about vitamin D for PCOS here. I summarize the most up-to-date science on Inositol for PCOS here.

3. Exercise

Professional guidelines recommend at least 150 minutes of physical activity per week for women with PCOS [39]. Others say that a minimum of 120 minutes per week of vigorous-intensity exercise should be the goal. High-intensity exercise is recommended. This type of exercise has the greatest impact on fitness, body weight, and insulin resistance [40]. The intensity, rather than the time spent appears to be the most important to health outcomes.

In my opinion, the best type of exercise for PCOS comes down to personal preferences. Being able to sustain a habit is the most important consideration. I say this because both strength training and aerobic exercise treat PCOS [41-44].

Exercise is a powerful antidepressant [45, 46]. It also has proven effects in the treatment of anxiety [47]. Given how common depression and anxiety is within the PCOS community, this in itself is a great reason to make time to work out [48, 49].

4. Sleep More

Remember how insulin resistance and inflammation are the underlying mechanisms of PCOS? Well, insufficient sleep is an independent risk factor for insulin resistance [50-52]. Sleep disturbance and duration are also associated with systemic inflammation [53].

If you want to know how to cure PCOS permanently at home, then the simplest answer is to spend more time in bed.

Sleep is a known problem within the PCOS community. Studies show that women with PCOS are approximately twice as likely to experience sleep disturbance [54].

Poor sleep has a big impact on a PCOS-friendly lifestyle. For example, when you get less sleep, you become less active [55]. Sleep also affects eating habits [56]. Studies have shown that getting more sleep reduces sugar cravings [57]. An extra 45 minutes of sleep at night can reduce how much sugar you eat [58].

So, it makes a lot of sense to do things that can prolong and improve your sleep. These include:

- Getting to bed early

- Keeping a cool sleeping environment

- Avoiding blue light exposure in the evening

- Doing some relaxation exercises before bed

If needed, it can also be worth experimenting with sleep-supporting supplements. Melatonin and 5-HTP are among the best options [59, 60].

5. Stress Less

Stress influences body weight and is a key cause of PCOS belly fat. Obesity causes stress and stress causes obesity [61]. It’s a vicious loop that needs to be broken.

Studies show that stress increases cortisol secretion. This causes the accumulation of body fat [62, 63]. Stress also changes how we behave making weight loss more difficult. For example, stress makes you more likely to eat poorly. It also decreases physical activity and shortens sleep [64].

Stress also affects fertility. And not just among women with PCOS. For example, A US study found that stressed women were twice as likely to suffer from infertility than their more chilled-out peers [45].

There are many sources of stress and even more ways to manage them. Some of the simplest steps require you to show yourself more kindness. Prioritize rest and recreation time. Reduce your workload. Stop setting unrealistically high expectations for yourself. Sleep more and get some exercise.

There are also many evidence-based stress management tools worth exploring. Cognitive-behavioral therapy and mindfulness-based stress reduction are among the most well-studied [65-68]. For people with a history of trauma, eye movement desensitization and reprocessing (EMDR) can be a life-changing therapy [69-71].

6. Check for Thyroid Dysfunction

As I mentioned at the top, PCOS is a collection of symptoms. But it’s not a disease. Because of this, it’s worth considering other factors that impact health and fertility. Diet, supplements, exercise, stress management, etc. all help. But in the presence of other untreated conditions, results are likely to be limited.

In my experience, unmanaged thyroid dysfunction is one of the main factors that limit the success of diet and lifestyle changes.

Autoimmune thyroid disease and PCOS share a bi-directional relationship [72]. Thyroid dysfunction creates escalating pro-inflammatory effects [73]. Even in the absence of PCOS, this can create PCOS-like symptoms. For example, subclinical hypothyroidism can cause metabolic changes that lead to weight gain [74]. Untreated hypothyroidism can also lead to subfertility, premature deliveries, and fetal deaths [75, 76].

Thyroid disorders are the most common hormone problems for women generally. Studies suggest around 8% of women are affected. But for PCOS women, this rate is approximately three times higher at 27%. What’s worse, nearly half of these cases are undiagnosed [77].

So, getting your thyroid checked is essential for women with PCOS.

It’s important when consulting with your doctor to request a full panel of tests. This should include TBG, T3, and reverse T3 biomarkers. Using only TSH and T4 biomarkers means that thyroid dysfunction can be missed.

7. Investigate Infections

The research in this field is still in its infancy. But there have been several associations drawn between PCOS and various infectious pathogens.

For example, one study found that chlamydia could, “contribute to the pathogenetic processes that lead to the metabolic and hormonal disorders of PCOS [78].” A possible association between Helicobacter pylori and PCOS was found in one small study of women in their twenties [79]. Gum disease caused by bacterial infections has also been associated with PCOS [87].

Other trials provide evidence that Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) and Cytomegalovirus (CMV) may be involved in the pathogenesis of PCOS [80]. The hypothesis here is that these viruses drive the chronic low-grade inflammation at the heart of a PCOS diagnosis. EBV and CMV are responsible for more than 95% of cases of infectious mononucleosis [81].

To diagnose and treat these infections, the care of a functional medicine or naturopathic doctor is required.

8. Avoid Endocrine Disruptors

I’ve already mentioned the role of prenatal exposure to endocrine-disrupting chemicals in the development of PCOS. But continued chronic exposure to this wide group of compounds may further exacerbate a PCOS diagnosis [82, 83].

The impact of EDCs on health and fertility is widespread. A recent review found connections between specific EDCs and a range of health outcomes. These included obesity, impaired glucose tolerance, diabetes, and breast cancer [84]. Their adverse impact on reproductive health is also well-established in the scientific literature [85].

For women that are trying to conceive, avoiding EDCs is especially important. Intrauterine exposure to EDCs can lay the foundation for disease in later life [86].

Some of the most common endocrine disruptors include:

- Pesticides (especially atrazine and organophosphates)

- Phthalates (DEHP, MEHP)

- Parabens

- Perchlorate

- Flame-retardant compounds (PBDEs, PFAS)

- Bisphenols (BPA, BPS, BPF, BPAF)

- Oxybenzone

- Glyphosate (RoundUp)

- Heavy metals (mercury, cadmium, lead, arsenic, aluminum)

Common household sources of EDCs include:

- Food and water

- Cookware

- Cleaning chemicals

- Textiles (clothing and furniture)

- Skin and beauty products

- Gardening products

For practical ways to reduce EDC exposure, download the EWG’s Guide to Endocrine Disruptors here.

9. Minimize Other Environmental Exposures

To manage PCOS, it’s important to minimize exposure to toxicants as much as is reasonably practical. This goes beyond EDCs. Water and air are the most common exposure pathways, yet these are often overlooked. If you want to lower inflammation, then improving the quality of your air and water can make a big difference.

Even though U.S. tap water supplies are considered to be among the safest in the world, water contamination can still occur. Drinking water is regulated. But there are many substances for which there are no applicable regulatory standards.

The consumer advocacy group, the EWG, maintains a tap water database. This online tool enables users to better understand the water quality in their local area. They also provide a water filter guide to help people select the most appropriate solution for their needs.

Poor indoor air also contains contaminants. These include molds, bacteria, viruses, animal dander, house dust, mites, and pollen.

These contaminants trigger allergic reactions and release disease-causing toxins. Exposure to mold and mycotoxins is especially hazardous, even for healthy people. For women with PCOS, mold toxicity can prevent progress and make symptoms worse despite an otherwise “clean” diet and lifestyle.

The US EPA recommends the following steps to reduce exposure to biological contaminants. These are sensible ways to further manage a PCOS diagnosis:

- Control the relative humidity in the home to 30-60%.

- Install externally vented exhaust fans in kitchens and bathrooms.

- Vent clothes dryers outdoors.

- Thoroughly clean and dry water-damaged carpets and building materials within 24 hours. Otherwise, consider removal and replacement.

- Keep the house clean to reduce allergy-causing agents.

- Ventilate the attic and crawl spaces to prevent moisture build-up.

- Minimize biological pollutants in basements.

The Bottom Line

There’s no cure for PCOS because PCOS isn’t a disease. It’s a collection of symptoms with clear underlying mechanisms. Poor gut health leading to chronic inflammation and insulin resistance cause PCOS symptoms. By managing these issues through diet and lifestyle changes you can improve your health and fertility.

For help starting a PCOS diet join my free 30-Day PCOS Diet Challenge. You can also download a free 3-Day Meal Plan here.

Because of the role of inflammation in PCOS, reducing exposure to toxicants can also improve symptoms. Avoid endocrine disruptors where possible. Take steps to improve drinking water and indoor air quality. If needed, work with a doctor to diagnose and treat thyroid dysfunction and chronic infections. These are both common diseases within the PCOS community.

Author

As a Nutritionist, I’m continuing my mission to help women like you, beat PCOS. Evidence-based diet and lifestyle interventions helped me overcome five years of infertility. I fell pregnant naturally after multiple failed IVF cycles. Along the way, my other PCOS symptoms went away too. This experience taught me how to combine the latest science with a pragmatic approach to habit change. I’ve now helped thousands of other women achieve life-changing results, and I love for you to be the next PCOS success story. Learn more about me and what I do here.

References

1Vink, J.M., et al., Heritability of polycystic ovary syndrome in a Dutch twin-family study. J Clin Endocrinol Metab, 2006. 91(6): p. 2100-4.

2Tata, B., et al., Elevated prenatal anti-Mullerian hormone reprograms the fetus and induces polycystic ovary syndrome in adulthood. Nature Medicine, 2018. 24(6): p. 834-+.

3Filippou, P. and R. Homburg, Is foetal hyperexposure to androgens a cause of PCOS? Human Reproduction Update, 2017. 23(4): p. 421-432.

4Raperport, C. and R. Homburg, The Source of Polycystic Ovarian Syndrome. Clinical Medicine Insights-Reproductive Health, 2019. 13.

5Fenichel, P., et al., Which origin for polycystic ovaries syndrome: Genetic, environmental or both? Annales D Endocrinologie, 2017. 78(3): p. 176-185.

6Hewlett, M., et al., Prenatal Exposure to Endocrine Disruptors: A Developmental Etiology for Polycystic Ovary Syndrome. Reproductive Sciences, 2017. 24(1): p. 19-27.

7Akgul, S., et al., THE ROLE OF ENDOCRINE DISRUPTORS IN THE AETIOPATHOGENESIS OF ADOLESCENT POLYCYSTIC OVARY SYNDROME. Journal of Adolescent Health, 2019. 64(2): p. S128-S129.

8Puttabyatappa, M., R.C. Cardoso, and V. Padmanabhan, Effect of maternal PCOS and PCOS-like phenotype on the offspring’s health. Molecular and Cellular Endocrinology, 2016. 435(C): p. 29-39.

9Bremer, A.A., Polycystic Ovary Syndrome in the Pediatric Population. Metabolic Syndrome and Related Disorders, 2010. 8(5): p. 375-394.

10Carvalho, L.M.L., et al., Polycystic Ovary Syndrome as a systemic disease with multiple molecular pathways: a narrative review. Endocr Regul, 2018. 52(4): p. 208-221.

11González, F., Inflammation in Polycystic Ovary Syndrome: underpinning of insulin resistance and ovarian dysfunction. Steroids, 2012. 77(4): p. 300-5.

12González, F., et al., Hyperandrogenism sensitizes mononuclear cells to promote glucose-induced inflammation in lean reproductive-age women. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab, 2012. 302(3): p. E297-306.

13Popovic, M., G. Sartorius, and M. Christ-Crain, Chronic low-grade inflammation in polycystic ovary syndrome: is there a (patho)-physiological role for interleukin-1? Seminars in Immunopathology, 2019. 41(4): p. 447-459.

14Rudnicka, E., et al., Chronic Low Grade Inflammation in Pathogenesis of PCOS. Int J Mol Sci, 2021. 22(7).

15Wang, J., et al., Hyperandrogenemia and insulin resistance: The chief culprit of polycystic ovary syndrome. Life Sciences, 2019. 236.

16Tremellen, K. and K. Pearce, Dysbiosis of Gut Microbiota (DOGMA)–a novel theory for the development of Polycystic Ovarian Syndrome. Med Hypotheses, 2012. 79(1): p. 104-12.

17He, F.F. and Y.M. Li, Role of gut microbiota in the development of insulin resistance and the mechanism underlying polycystic ovary syndrome: a review. J Ovarian Res, 2020. 13(1): p. 73.

18Barrea, L., et al., Source and amount of carbohydrate in the diet and inflammation in women with polycystic ovary syndrome. Nutr Res Rev, 2018. 31(2): p. 291-301.

19Sivasankari, R. and B. Usha, Reshaping the Gut Microbiota Through Lifestyle Interventions in Women with PCOS: A Review. Indian J Microbiol, 2022. 62(3): p. 351-363.

20Szczuko, M., et al., Quantitative assessment of nutrition in patients with polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS). Rocz Panstw Zakl Hig, 2016. 67(4): p. 419-426.

21Wakeman, M. and D.T. Archer, Metformin and Micronutrient Status in Type 2 Diabetes: Does Polypharmacy Involving Acid-Suppressing Medications Affect Vitamin B12 Levels? Diabetes Metab Syndr Obes, 2020. 13: p. 2093-2108.

22Thorp, V.J., Effect of oral contraceptive agents on vitamin and mineral requirements. J Am Diet Assoc, 1980. 76(6): p. 581-4.

23Webb, J.L., Nutritional effects of oral contraceptive use: a review. J Reprod Med, 1980. 25(4): p. 150-6.

24Palmery, M., et al., Oral contraceptives and changes in nutritional requirements. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci, 2013. 17(13): p. 1804-13.

25Aroda, V.R., et al., Long-term Metformin Use and Vitamin B12 Deficiency in the Diabetes Prevention Program Outcomes Study. J Clin Endocrinol Metab, 2016. 101(4): p. 1754-61.

26Ting, R.Z., et al., Risk factors of vitamin B(12) deficiency in patients receiving metformin. Arch Intern Med, 2006. 166(18): p. 1975-9.

27Bauman, W.A., et al., Increased intake of calcium reverses vitamin B12 malabsorption induced by metformin. Diabetes Care, 2000. 23(9): p. 1227-31.

28Kozyraki, R. and O. Cases, Vitamin B12 absorption: mammalian physiology and acquired and inherited disorders. Biochimie, 2013. 95(5): p. 1002-7.

29Wulffelé, M.G., et al., Effects of short-term treatment with metformin on serum concentrations of homocysteine, folate and vitamin B12 in type 2 diabetes mellitus: a randomized, placebo-controlled trial. J Intern Med, 2003. 254(5): p. 455-63.

30Quadros, E.V., Advances in the understanding of cobalamin assimilation and metabolism. Br J Haematol, 2010. 148(2): p. 195-204.

31Reinstatler, L., et al., Association of biochemical B₁₂ deficiency with metformin therapy and vitamin B₁₂ supplements: the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 1999-2006. Diabetes Care, 2012. 35(2): p. 327-33.

32Ghasemi Fard, S., et al., How does high DHA fish oil affect health? A systematic review of evidence. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr, 2019. 59(11): p. 1684-1727.

33Tabrizi, R., et al., The effects of curcumin-containing supplements on biomarkers of inflammation and oxidative stress: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Phytother Res, 2019. 33(2): p. 253-262.

34Ju, J., et al., Efficacy and safety of berberine for dyslipidaemias: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials. Phytomedicine, 2018. 50: p. 25-34.

35Rondanelli, M., et al., Polycystic ovary syndrome management: a review of the possible amazing role of berberine. Arch Gynecol Obstet, 2020. 301(1): p. 53-60.

36Wei, W., et al., A clinical study on the short-term effect of berberine in comparison to metformin on the metabolic characteristics of women with polycystic ovary syndrome. Eur J Endocrinol, 2012. 166(1): p. 99-105.

37Xie, L., et al., The Effect of Berberine on Reproduction and Metabolism in Women with Polycystic Ovary Syndrome: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Control Trials. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med, 2019. 2019: p. 7918631.

38Li, M.F., X.M. Zhou, and X.L. Li, The Effect of Berberine on Polycystic Ovary Syndrome Patients with Insulin Resistance (PCOS-IR): A Meta-Analysis and Systematic Review. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med, 2018. 2018: p. 2532935.

39Woodward, A., M. Klonizakis, and D. Broom, Exercise and Polycystic Ovary Syndrome. Adv Exp Med Biol, 2020. 1228: p. 123-136.

40Patten, R.K., et al., Exercise Interventions in Polycystic Ovary Syndrome: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Front Physiol, 2020. 11: p. 606.

41Cheema, B.S., L. Vizza, and S. Swaraj, Progressive resistance training in polycystic ovary syndrome: can pumping iron improve clinical outcomes? Sports Med, 2014. 44(9): p. 1197-207.

42Almenning, I., et al., Effects of High Intensity Interval Training and Strength Training on Metabolic, Cardiovascular and Hormonal Outcomes in Women with Polycystic Ovary Syndrome: A Pilot Study. PLoS One, 2015. 10(9): p. e0138793.

43Covington, J.D., et al., Higher circulating leukocytes in women with PCOS is reversed by aerobic exercise. Biochimie, 2016. 124: p. 27-33.

44Shele, G., J. Genkil, and D. Speelman, A Systematic Review of the Effects of Exercise on Hormones in Women with Polycystic Ovary Syndrome. J Funct Morphol Kinesiol, 2020. 5(2).

45Schuch, F.B. and B. Stubbs, The Role of Exercise in Preventing and Treating Depression. Curr Sports Med Rep, 2019. 18(8): p. 299-304.

46Wegner, M., et al., Effects of exercise on anxiety and depression disorders: review of meta- analyses and neurobiological mechanisms. CNS Neurol Disord Drug Targets, 2014. 13(6): p. 1002-14.

47Aylett, E., N. Small, and P. Bower, Exercise in the treatment of clinical anxiety in general practice – a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Health Serv Res, 2018. 18(1): p. 559.

48Barry, J.A., A.R. Kuczmierczyk, and P.J. Hardiman, Anxiety and depression in polycystic ovary syndrome: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Hum Reprod, 2011. 26(9): p. 2442-51.

49Jedel, E., et al., Anxiety and depression symptoms in women with polycystic ovary syndrome compared with controls matched for body mass index. Hum Reprod, 2010. 25(2): p. 450-6.

50Van Cauter, E., Sleep disturbances and insulin resistance. Diabet Med, 2011. 28(12): p. 1455-62.

51Nedeltcheva, A.V., et al., Exposure to recurrent sleep restriction in the setting of high caloric intake and physical inactivity results in increased insulin resistance and reduced glucose tolerance. J Clin Endocrinol Metab, 2009. 94(9): p. 3242-50.

52Tasali, E., et al., Impact of obstructive sleep apnea on insulin resistance and glucose tolerance in women with polycystic ovary syndrome. J Clin Endocrinol Metab, 2008. 93(10): p. 3878-84.

53Irwin, M.R., R. Olmstead, and J.E. Carroll, Sleep Disturbance, Sleep Duration, and Inflammation: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Cohort Studies and Experimental Sleep Deprivation. Biol Psychiatry, 2016. 80(1): p. 40-52.

54Moran, L.J., et al., Sleep disturbances in a community-based sample of women with polycystic ovary syndrome. Hum Reprod, 2015. 30(2): p. 466-72.

55Schmid, S.M., et al., Short-term sleep loss decreases physical activity under free-living conditions but does not increase food intake under time-deprived laboratory conditions in healthy men. Am J Clin Nutr, 2009. 90(6): p. 1476-82.

56Blumfield, M.L., et al., Dietary disinhibition mediates the relationship between poor sleep quality and body weight. Appetite, 2018. 120: p. 602-608.

57Smith, S.L., M.J. Ludy, and R.M. Tucker, Changes in taste preference and steps taken after sleep curtailment. Physiol Behav, 2016. 163: p. 228-233.

58Al Khatib, H.K., et al., Sleep extension is a feasible lifestyle intervention in free-living adults who are habitually short sleepers: a potential strategy for decreasing intake of free sugars? A randomized controlled pilot study. Am J Clin Nutr, 2018. 107(1): p. 43-53.

59Fatemeh, G., et al., Effect of melatonin supplementation on sleep quality: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J Neurol, 2022. 269(1): p. 205-216.

60Maffei, M.E., 5-Hydroxytryptophan (5-HTP): Natural Occurrence, Analysis, Biosynthesis, Biotechnology, Physiology and Toxicology. Int J Mol Sci, 2020. 22(1).

61Kumar, R., M.R. Rizvi, and S. Saraswat, Obesity and Stress: A Contingent Paralysis. Int J Prev Med, 2022. 13: p. 95.

62Donoho, C.J., et al., Stress and abdominal fat: preliminary evidence of moderation by the cortisol awakening response in Hispanic peripubertal girls. Obesity (Silver Spring), 2011. 19(5): p. 946-52.

63Epel, E.S., et al., Stress and body shape: stress-induced cortisol secretion is consistently greater among women with central fat. Psychosom Med, 2000. 62(5): p. 623-32.

64Tomiyama, A.J., Stress and Obesity. Annu Rev Psychol, 2019. 70: p. 703-718.

65Khoury, B., et al., Mindfulness-based stress reduction for healthy individuals: A meta-analysis. J Psychosom Res, 2015. 78(6): p. 519-28.

66van Dis, E.A.M., et al., Long-term Outcomes of Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for Anxiety-Related Disorders: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. JAMA Psychiatry, 2020. 77(3): p. 265-273.

67Carpenter, J.K., et al., Cognitive behavioral therapy for anxiety and related disorders: A meta-analysis of randomized placebo-controlled trials. Depress Anxiety, 2018. 35(6): p. 502-514.

68González-Valero, G., et al., Use of Meditation and Cognitive Behavioral Therapies for the Treatment of Stress, Depression and Anxiety in Students. A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Int J Environ Res Public Health, 2019. 16(22).

69Chen, L., et al., Eye movement desensitization and reprocessing versus cognitive-behavioral therapy for adult posttraumatic stress disorder: systematic review and meta-analysis. J Nerv Ment Dis, 2015. 203(6): p. 443-51.

70Novo Navarro, P., et al., 25 years of Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing (EMDR): The EMDR therapy protocol, hypotheses of its mechanism of action and a systematic review of its efficacy in the treatment of post-traumatic stress disorder. Rev Psiquiatr Salud Ment (Engl Ed), 2018. 11(2): p. 101-114.

71Valiente-Gómez, A., et al., EMDR beyond PTSD: A Systematic Literature Review. Front Psychol, 2017. 8: p. 1668.

72Singla, R., et al., Thyroid disorders and polycystic ovary syndrome: An emerging relationship. Indian J Endocrinol Metab, 2015. 19(1): p. 25-9.

73Weetman, A.P., An update on the pathogenesis of Hashimoto’s thyroiditis. J Endocrinol Invest, 2021. 44(5): p. 883-890.

74Walczak, K. and L. Sieminska, Obesity and Thyroid Axis. Int J Environ Res Public Health, 2021. 18(18).

75Koyyada, A. and P. Orsu, Role of hypothyroidism and associated pathways in pregnancy and infertility: Clinical insights. Tzu Chi Med J, 2020. 32(4): p. 312-317.

76Krassas, G.E., K. Poppe, and D. Glinoer, Thyroid function and human reproductive health. Endocr Rev, 2010. 31(5): p. 702-55.

77Garelli, S., et al., High prevalence of chronic thyroiditis in patients with polycystic ovary syndrome. European Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology and Reproductive Biology, 2013. 169(2): p. 248-251.

78Morin-Papunen, L.C., et al., Chlamydia antibodies and self-reported symptoms of oligo-amenorrhea and hirsutism: a new etiologic factor in polycystic ovary syndrome? Fertil Steril, 2010. 94(5): p. 1799-804.

79Yavasoglu, I., et al., A novel association between polycystic ovary syndrome and Helicobacter pylori. Am J Med Sci, 2009. 338(3): p. 174-7.

80Alabassi, H.K., ZHM. ; Mahmood, MM.; AL-Kubisi, MI., The Possible Etiological Role of CMV & EBV Latent Infections in Polycystic Ovary Syndrome Iraqi patients. Systematic Reviews in Pharmacy, 2020.

81Hurt, C. and D. Tammaro, Diagnostic evaluation of mononucleosis-like illnesses. Am J Med, 2007. 120(10): p. 911.e1-8.

82Palioura, E. and E. Diamanti-Kandarakis, Industrial endocrine disruptors and polycystic ovary syndrome. J Endocrinol Invest, 2013. 36(11): p. 1105-11.

83Šimková, M., et al., Endocrine disruptors, obesity, and cytokines – how relevant are they to PCOS? Physiol Res, 2020. 69(Suppl 2): p. S279-s293.

84Kahn, L.G., et al., Endocrine-disrupting chemicals: implications for human health. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol, 2020. 8(8): p. 703-718.

85Piazza, M.J. and A.A. Urbanetz, Environmental toxins and the impact of other endocrine disrupting chemicals in women’s reproductive health. JBRA Assist Reprod, 2019. 23(2): p. 154-164.

86Predieri, B., C.A.D. Alves, and L. Iughetti, New insights on the effects of endocrine-disrupting chemicals on children. J Pediatr (Rio J), 2022. 98 Suppl 1(Suppl 1): p. S73-s85.

87Kellesarian, S.V., et al., Association between periodontal disease and polycystic ovary syndrome: a systematic review. Int J Impot Res, 2017. 29(3): p. 89-95.

As a Nutritionist, I’m continuing my mission to help women like you, beat PCOS. Evidence-based diet and lifestyle interventions helped me overcome five years of infertility. I fell pregnant naturally after multiple failed IVF cycles. Along the way, my other PCOS symptoms went away too. This experience taught me how to combine the latest science with a pragmatic approach to habit change. I’ve now helped thousands of other women achieve life-changing results, and I love for you to be the next PCOS success story. Learn more about me and what I do here.