Hormonal contraceptives are one of the most widely used treatments for PCOS. Yet few people are warned about the risks.

This article sets the record straight. I’ve summarized what the science says, so you can make an informed choice.

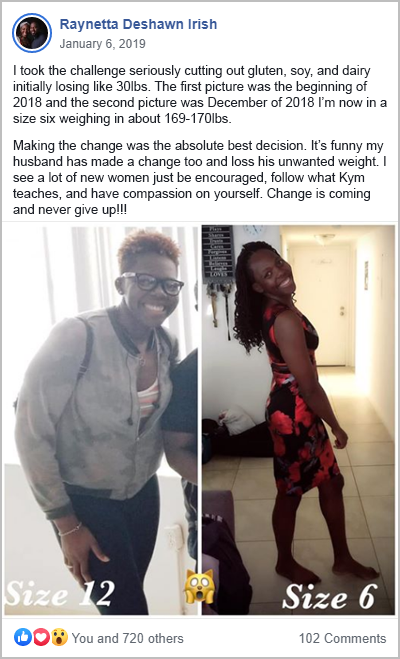

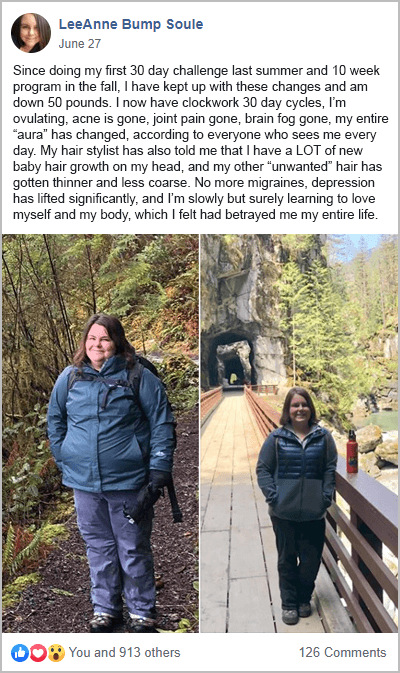

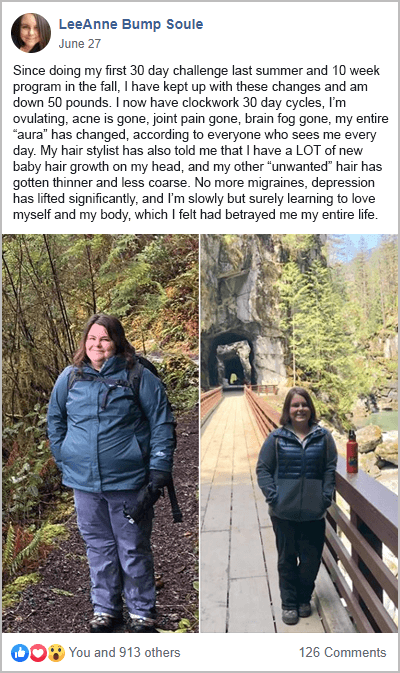

The most important message here is that a PCOS diet is key to controlling your symptoms. Birth control only masks the symptoms. With this in mind, take action today by joining my free 30-Day PCOS Diet Challenge. Or try this free 3-Day meal plan.

Here are 9 reasons to avoid birth control for PCOS and what you should do instead.

1. Birth Control Masks Your Symptoms

Before we get into the hazards of birth control for PCOS, it’s important to understand its limitations. Hormonal contraceptives mask symptoms. They don’t address the underlying causes of PCOS hormone imbalances.

The synthetic forms of estrogen and progesterone used in birth control force a monthly bleed. But they’re also switching off ovulation and healthy natural hormone regulation. This kind of band-aid solution can give you a false sense of security. Even though you have a “regular period”, your health and fertility can continue to deteriorate without you being aware of it.

2. It’s Bad For Metabolic Health

Birth control may harm metabolic health. For women with PCOS, this is particularly bad news. PCOS women have increased risks for metabolic disorders. This includes obesity, insulin resistance, type 2 diabetes, liver disease, and hypertension. Taking birth control on top of this may make matters worse.

A systematic review of birth control for women with PCOS found many health benefits in support of this intervention. But they also found that “most preparations increase… triglycerides” [1]. Similar studies found that low-density lipoprotein levels were also adversely affected. These effects were found across a range of hormonal contraceptives [2].

Regarding effects on glucose metabolism and insulin sensitivity, the science is less clear. One systematic review found that combined oral contraceptives did not make glucose levels worse. They found that it may in fact improve insulin sensitivity [1]. But this is contrary to other studies where oral contraceptives reduced insulin sensitivity. This has been shown both in women with PCOS [3] and in young healthy, normal-weight women [4, 5].

The key take-home here is that we don’t know for sure. But there’s compelling evidence showing a risk to metabolic health from taking birth control. This is worth keeping in mind when speaking with your doctor.

3. Causes Chronic Inflammation And Pill-Induced PCOS

It’s common to read that the cause of PCOS is unknown. But this level of academic caution seems unhelpful. We know that genetic, epigenetic, and environmental factors contribute to the development of PCOS [6-8]. It’s also known that PCOS hormone balances are caused by inflammation, insulin resistance, and elevated androgens [9-12].

The mechanisms at play here are complex. But chronic inflammation is one of the underlying causes of PCOS. This is a big reason to avoid birth control. Birth control drives inflammation [13].

Take this randomized, placebo-controlled trial for example. Researchers prescribed women with PCOS either lifestyle modification alone or birth control. Both of these interventions reduced androgen levels. But only the group of women taking birth control saw an increase in inflammation [14].

Hormonal contraceptives appear to drive inflammation in women that don’t have PCOS too. That’s why birth control is associated with many autoimmune disorders. These include Crohn’s disease, Lupus, and interstitial cystitis [15].

This may, in part, explain the phenomenon of pill-induced PCOS. This is a condition where women who had regular periods before being on birth control, find their cycle doesn’t return once they go off it.

4. Birth Control Depletes Nutrients

The impact of hormonal contraceptives on nutrient status is straightforward. It’s been a concern since at least the 1970s [16, 17]. The World Health Organization notes that nutrient deficiencies from the use of birth control are “.. of high clinical relevance and should, therefore, receive great attention”. This includes vitamins B2, B6, B9 (folic acid), B12, C, and E. Depletions of magnesium, selenium, and zinc have also been identified as nutrients of concern [18].

If you’re seeking better health then these nutrients are essential. This is why clinicians are told to consider supplements when prescribing birth control.

Unfortunately, this sage advice is seldom heeded by doctors. I’ve surveyed over 500 women in my PCOS community about this. Less than 2% were advised to check their nutrient levels within six months of starting birth control. More than 96% said they had never had their nutrient status checked at all. Yikes!

5. Has Negative Impacts On Mental Health

When I learned how birth control affects your mental health, I had a massive “Ah Ha!” moment. I started birth control in my teens to manage my absent periods. Within a year, I’d advanced to antidepressants.

To be fair, the scientific evidence linking birth control to depression is conflicted and confusing. A review by the American Journal of Psychiatry (AMJP) suggests that birth control does not cause depression [19].

But others disagree.

A lot of this comes down to the patients studied. For example, the AMJP review looked only at women with mental illness. This nuance is often obscured by people who cite this study. The poor quality of many studies also muddies the waters. Many rely on iffy methods like self-reporting, recall, and insufficient numbers of patients [20].

One of the most powerful studies conducted to date included 1,061,997 women. The researchers found that women who took birth control were more likely to go on antidepressants at a later date (like I was) [21].

The differences were dependent on the type of birth control. Women who took combined oral contraceptives were 23% more likely to take antidepressants at a later date.

Later antidepressant use was higher for women using vaginal rings. In this case, the chance of going on antidepressants went up by 60%. Progestogen-only pills, a patch, and levonorgestrel IUDs sat somewhere between.

Findings like this have led at least one psychiatrist I know of to describe birth control as a “gateway drug to antidepressants”.

Even more concerning is the link between birth control use and suicide. A systematic review and meta-analysis showed hormonal contraceptive use was associated with suicide [22]. Other studies have found that this risk is highest in young women. Especially during their first few months of starting treatment [23].

One powerful study followed 3.9 million women for more than eight years on average. In this study, a three-fold increased risk of suicide was observed in birth control users [24]. Oral progestin-only products, vaginal rings, and patches were worse than combined oral contraceptive pills.

Association does not infer causation. But researchers are unpacking a potential mechanism that explains these observations. Studies show that the risk may be greatest if you first started taking birth control during your teens like I did [25].

6. Birth Control Increases Cancer Risks

Hormonal contraceptive use is associated with a small increased risk of breast cancer.

A cohort of 1.8 million women was followed on average for 10.9 years by Danish researchers. They found that women who had recently taken birth control were 20% more likely to develop breast cancer [26].

This risk increased with long-term use. For women that were on the pill for more than 5 years, risks remained higher even after stopping treatment. This was the case for oral combination contraceptives as well as hormonal IUDs. Other studies looking at levonorgestrel intrauterine systems have supported this finding [27].

It’s worth noting that these increased risks are small. According to the Danish study, hormonal contraceptive users have around one extra case of breast cancer for every 7690 women.

7. It Increases Your Kids’ Risk For ADHD

Maternal birth control use was long suspected of increasing risks for childhood attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). But there was little evidence to support this.

A massive Danish study sought to answer this question. They took health data from a million children born between 1998 and 2014. They then compared this dataset to their mothers’ prescriptions for hormonal contraceptives. They found that ADHD rates in children were higher if their mothers had previously used hormonal contraceptives [28].

The risk was highest with non-oral progestin products. Things like the Depo-Provera injection, and the Mirena, Kyleena, Skyla, or Liletta IUD. These forms of birth control doubled the risk of ADHD if the mother took them before pregnancy. The risk tripled if she accidentally kept taking them during pregnancy.

8. It Increases The Risk Of Blood Clotting Issues

PCOS is associated with an increased risk of blood clotting disorders [29]. This is preventable and treatable if discovered early. But it remains a serious health issue that can cause disability, and even, death.

Obesity and insulin resistance are key risk factors for blood clotting disorders [30]. Chronic inflammation is another [31].

The link between deep vein thrombosis and birth control has been well studied. According to a Danish study, women who used vaginal rings had a 6.5 times increased risk of deep vein thrombosis. For women using contraceptive patches, the increased risk was 7.5 times [32]. Subcutaneous implants also had a small increase in risks.

9. It’s A Harmful Preconception Treatment

There is a significant knowledge gap among physicians treating women with PCOS [33].

The use of oral contraceptives as a preconception treatment illustrates this finding. The idea behind this treatment is that the pill will suppress the over-production of androgens. In theory, this should then kick-start ovulation upon discontinuation.

The problem with this approach is that it’s based on outdated science.

Studies have shown that taking birth control in preparation for fertility treatment may do more harm than good. Preconception birth control does not appear to improve ovulation or live birth rates [34]. But it increases the risk of developing metabolic syndrome [35].

Birth Control Alternatives

There are several good alternatives to hormonal contraceptives for preventing pregnancy.

Fertility Awareness

Fertility awareness is the healthiest way to prevent pregnancy. You’ll likely only want to use this method after you’ve achieved a regular cycle through diet and lifestyle interventions.

Fertility awareness requires that you pay attention to your cycle. By observing your cervical mucus and basal temperature you can predict the days you’ll be fertile. This typically occurs over a six-day window each month. During this time, you can abstain from intercourse, or use one of the barrier methods described below.

When used correctly, fertility awareness-based methods can be as reliable as other forms of birth control. Studies on fertility-awareness methods have found unplanned pregnancy rates of 0.6 per 100 women [36].

Condoms

If you currently have irregular periods, then male condoms are likely the best option for preventing pregnancy. Male condoms have an efficacy rate of 98%. They are also the only form of contraceptive that can prevent sexually transmitted diseases. Female condoms are also a good option. The efficacy is slightly less than that of male condoms, but they’re still considered highly effective.

Diaphragms

Diaphragms with spermicide gels are further down my list of preferred contraceptives. They are less effective at preventing pregnancy than condoms. Studies also show that they alter the vaginal microbiome and may predispose women to urinary tract infections [37-39].

Copper IUD

The copper IUD (a.k.a. Paragard) is convenient and effective at preventing pregnancy. Unlike levonorgestrel IUDs, a copper IUD doesn’t impact your hormones. When you take it out, your fertility returns to normal. But it’s also known to be bad for your vaginal microbiome. Studies show that the copper IUD may increase your chances of getting bacterial vaginosis [40]. One of my favorite authors on women’s reproductive health has further criticism of copper IUDs. Lara Briden says that these devices can cause heavier periods. Copper IUDs can also increase the risk of pelvic inflammatory disease.

A Better Way To Control PCOS Symptoms

As I’ve described above, insulin resistance and chronic inflammation are the underlying drivers of all PCOS symptoms. These are the cause of the hormone imbalances that birth control tries to “fix”.

Rather than mask the symptoms, women with PCOS are better served by lifestyle interventions. A PCOS-friendly diet is the most essential of these steps.

Changing the way you eat improves insulin regulation. This can be achieved by choosing foods with a low glycemic index. Optimizing macronutrient ratios is also very important. For most women, this means being mindful of sugar and carb-rich foods.

Systemic inflammation can be reduced by avoiding certain ingredients. This includes foods that can damage the intestinal wall lining. Better gut health is also promoted through foods that support a diverse gut microbiome.

You can learn more about a PCOS diet here. By joining my free 30-Day PCOS Diet Challenge you’ll gain the skills and resources you need to put a PCOS diet into practice. The Challenge includes weekly meal plans, recipes, shopping lists, and video lessons.

You can also download this free 3-day meal plan to get started today.

The Bottom Line

Hormonal contraceptives negatively affect your metabolic health. They promote inflammation and cause nutritional deficiencies. Birth control has been linked to increased risks for depression, suicide, and cancer. Taking these hormones before conception may also harm your child’s development.

Yet, birth control is still the drug of choice for the treatment of PCOS. It’s also commonly used by women with PCOS to prevent unwanted pregnancy.

There are much safer ways to address these problems. Using non-hormonal contraceptives is the best option for preventing pregnancy. And if you’re looking for a way to manage your symptoms, then diet and lifestyle changes will get you the best results.

FAQ: Types Of Hormonal Contraceptives

Combined Oral Contraceptives. Combined oral contraceptives are the most commonly prescribed type of birth control for PCOS. They include both estrogen and progestogen (progestin). Common brands are included in the table below.

| Common brand names for combined oral contraceptives. | |||

|---|---|---|---|

|

Alesse Apri Aranelle Aviane Azurette Beyaz Caziant Desogen Enpresse |

Estrostep Fe Gianvi Kariva Lessina Levlite Levora Loestrin Lybrel Mircette |

Natazia Nordette Ocella Low-Ogestrel Lo Ovral Ortho-Novum Ortho Tri-Cyclen Previfem Reclipsen |

Safyral Seasonale Seasonique TriNessa Velivet Yasmin Yaz |

| Common brand names for combined oral contraceptives. | |

|---|---|

|

Alesse Apri Aranelle Aviane Azurette Beyaz Caziant Desogen Enpresse Estrostep Fe Gianvi Kariva Lessina Levlite Levora Loestrin Lybrel |

Mircette Natazia Nordette Ocella Low-Ogestrel Lo Ovral Ortho-Novum Ortho Tri-Cyclen Previfem Reclipsen Safyral Seasonale Seasonique TriNessa Velivet Yasmin Yaz |

Oral Progestin-Only Pills. Oral progestin-only pills are often known as the “mini-pill”. This includes products like Camila, Errin, Heather, Jolivette, Nor-Q.D, Norethindrone, Slynd, Micronor, and Ovrette.

Levonorgestrel IUD. Levonorgestrel IUDs are small t-shaped devices that are fitted inside the uterus. These products slowly release the hormone levonorgestrel to prevent pregnancy. Mirena, Kyleena, Skyla, and Liletta are the most popular levonorgestrel IUD products.

Vaginal Rings. The vaginal ring is a soft plastic device that women can insert and remove themselves. It’s left in place for 3 weeks to release estrogen and progestogen. These are the same hormones used in combined oral contraceptives. NuvaRing is the most commonly used vaginal ring.

Contraceptive Patches. A contraceptive patch administers estrogen and progestogen through the skin. Xulane, Twirla, and Evra are the main brands of contraceptive patches.

Subcutaneous Implants. A contraceptive implant is inserted under the skin on the inside of the arm. These include products such as Norplant, Jadelle (Norplant II), Implanon, Nexplanon, Sino-implant (II), Zarin, Femplant, and Trust.

Contraceptive Injection. The contraceptive injection uses the synthetic hormone Depot medroxyprogesterone acetate (DMPA). The contraceptive is injected into the buttock or upper arm where it slowly releases the DMPA. Common brands include Depo-Provera, Depo-Ralovera, and Noristerat.

Author

As a Nutritionist, I’m continuing my mission to help women like you, beat PCOS. Evidence-based diet and lifestyle interventions helped me overcome five years of infertility. I fell pregnant naturally after multiple failed IVF cycles. Along the way, my other PCOS symptoms went away too. This experience taught me how to combine the latest science with a pragmatic approach to habit change. I’ve now helped thousands of other women achieve life-changing results, and I love for you to be the next PCOS success story. Learn more about me and what I do here.

References

1de Medeiros, S.F., Risks, benefits size and clinical implications of combined oral contraceptive use in women with polycystic ovary syndrome. Reprod Biol Endocrinol, 2017. 15(1): p. 93.

2Amiri, M., et al., Effects of oral contraceptives on metabolic profile in women with polycystic ovary syndrome: A meta-analysis comparing products containing cyproterone acetate with third generation progestins. Metabolism, 2017. 73: p. 22-35.

3Mastorakos, G., et al., Effects of two forms of combined oral contraceptives on carbohydrate metabolism in adolescents with polycystic ovary syndrome. Fertil Steril, 2006. 85(2): p. 420-7.

4Piltonen, T., et al., Oral, transdermal and vaginal combined contraceptives induce an increase in markers of chronic inflammation and impair insulin sensitivity in young healthy normal-weight women: a randomized study. Hum Reprod, 2012. 27(10): p. 3046-56.

5Petersen, K.R., Pharmacodynamic effects of oral contraceptive steroids on biochemical markers for arterial thrombosis. Studies in non-diabetic women and in women with insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. Dan Med Bull, 2002. 49(1): p. 43-60.

6Raperport, C. and R. Homburg, The Source of Polycystic Ovarian Syndrome. Clinical Medicine Insights-Reproductive Health, 2019. 13.

7Fenichel, P., et al., Which origin for polycystic ovaries syndrome: Genetic, environmental or both? Annales D Endocrinologie, 2017. 78(3): p. 176-185.

8Bremer, A.A., Polycystic Ovary Syndrome in the Pediatric Population. Metabolic Syndrome and Related Disorders, 2010. 8(5): p. 375-394.

9Rostamtabar, M., et al., Pathophysiological roles of chronic low-grade inflammation mediators in polycystic ovary syndrome. J Cell Physiol, 2021. 236(2): p. 824-838.

10Hu, C., et al., Immunophenotypic Profiles in Polycystic Ovary Syndrome. Mediators Inflamm, 2020. 2020: p. 5894768.

11Popovic, M., G. Sartorius, and M. Christ-Crain, Chronic low-grade inflammation in polycystic ovary syndrome: is there a (patho)-physiological role for interleukin-1? Seminars in Immunopathology, 2019. 41(4): p. 447-459.

12Wang, J., et al., Hyperandrogenemia and insulin resistance: The chief culprit of polycystic ovary syndrome. Life Sciences, 2019. 236.

13de Medeiros, S.F., et al., Combined Oral Contraceptive Effects on Low-Grade Chronic Inflammatory Mediators in Women with Polycystic Ovary Syndrome: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Int J Inflam, 2018. 2018: p. 9591509.

14Hoeger, K., et al., The impact of metformin, oral contraceptives, and lifestyle modification on polycystic ovary syndrome in obese adolescent women in two randomized, placebo-controlled clinical trials. J Clin Endocrinol Metab, 2008. 93(11): p. 4299-306.

15Williams, W.V., Hormonal contraception and the development of autoimmunity: A review of the literature. Linacre Q, 2017. 84(3): p. 275-295.

16Thorp, V.J., Effect of oral contraceptive agents on vitamin and mineral requirements. J Am Diet Assoc, 1980. 76(6): p. 581-4.

17Webb, J.L., Nutritional effects of oral contraceptive use: a review. J Reprod Med, 1980. 25(4): p. 150-6.

18Palmery, M., et al., Oral contraceptives and changes in nutritional requirements. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci, 2013. 17(13): p. 1804-13.

19McCloskey, L.R., et al., Contraception for Women With Psychiatric Disorders. Am J Psychiatry, 2020: p. appiajp202020020154.

20Schaffir, J., B.L. Worly, and T.L. Gur, Combined hormonal contraception and its effects on mood: a critical review. Eur J Contracept Reprod Health Care, 2016. 21(5): p. 347-55.

21Skovlund, C.W., et al., Association of Hormonal Contraception With Depression. JAMA Psychiatry, 2016. 73(11): p. 1154-1162.

22Pérez-López, F.R., et al., Hormonal contraceptives and the risk of suicide: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol, 2020. 251: p. 28-35.

23Edwards, A.C., et al., Oral contraceptive use and risk of suicidal behavior among young women. Psychol Med, 2020: p. 1-8.

24Skovlund, C.W., et al., Association of Hormonal Contraception With Suicide Attempts and Suicides. Am J Psychiatry, 2018. 175(4): p. 336-342.

25Sharma, R., et al., Oral contraceptive use, especially during puberty, alters resting state functional connectivity. Horm Behav, 2020. 126: p. 104849.

26Mørch, L.S., et al., Contemporary Hormonal Contraception and the Risk of Breast Cancer. N Engl J Med, 2017. 377(23): p. 2228-2239.

27Conz, L., et al., Levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system and breast cancer risk: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand, 2020. 99(8): p. 970-982.

28Hemmingsen, C.H., et al., Maternal use of hormonal contraception and risk of childhood ADHD: a nationwide population-based cohort study. Eur J Epidemiol, 2020. 35(9): p. 795-805.

29Glintborg, D., et al., Increased thrombin generation in women with polycystic ovary syndrome: A pilot study on the effect of metformin and oral contraceptives. Metabolism, 2015. 64(10): p. 1272-8.

30Van Schouwenburg, I.M., et al., Insulin resistance and risk of venous thromboembolism: results of a population-based cohort study. J Thromb Haemost, 2012. 10(6): p. 1012-8.

31Aksu, K., A. Donmez, and G. Keser, Inflammation-induced thrombosis: mechanisms, disease associations and management. Curr Pharm Des, 2012. 18(11): p. 1478-93.

32Lidegaard, O., et al., Venous thrombosis in users of non-oral hormonal contraception: follow-up study, Denmark 2001-10. Bmj, 2012. 344: p. e2990.

33Dokras, A., et al., Gaps in knowledge among physicians regarding diagnostic criteria and management of polycystic ovary syndrome. Fertil Steril, 2017. 107(6): p. 1380-1386.e1.

34Legro, R.S., et al., Benefit of Delayed Fertility Therapy With Preconception Weight Loss Over Immediate Therapy in Obese Women With PCOS. J Clin Endocrinol Metab, 2016. 101(7): p. 2658-66.

35Legro, R.S., et al., Randomized Controlled Trial of Preconception Interventions in Infertile Women With Polycystic Ovary Syndrome. J Clin Endocrinol Metab, 2015. 100(11): p. 4048-58.

36Hampton, K.D., D. Mazza, and J.M. Newton, Fertility-awareness knowledge, attitudes, and practices of women seeking fertility assistance. J Adv Nurs, 2013. 69(5): p. 1076-84.

37Gupta, K., et al., Effects of contraceptive method on the vaginal microbial flora: a prospective evaluation. J Infect Dis, 2000. 181(2): p. 595-601.

38Hooton, T.M., P.L. Roberts, and W.E. Stamm, Effects of recent sexual activity and use of a diaphragm on the vaginal microflora. Clin Infect Dis, 1994. 19(2): p. 274-8.

39Hooton, T.M., et al., Association between bacterial vaginosis and acute cystitis in women using diaphragms. Arch Intern Med, 1989. 149(9): p. 1932-6.

40Achilles, S.L., et al., Impact of contraceptive initiation on vaginal microbiota. Am J Obstet Gynecol, 2018. 218(6): p. 622.e1-622.e10.

As a Nutritionist, I’m continuing my mission to help women like you, beat PCOS. Evidence-based diet and lifestyle interventions helped me overcome five years of infertility. I fell pregnant naturally after multiple failed IVF cycles. Along the way, my other PCOS symptoms went away too. This experience taught me how to combine the latest science with a pragmatic approach to habit change. I’ve now helped thousands of other women achieve life-changing results, and I love for you to be the next PCOS success story. Learn more about me and what I do here.